Archive for the ‘irish’ Category

Wider Wake

I’ve noticed something reading Finnegans Wake for the first time – I call it ‘Wake Hang-over’. During the Corona lockdown I begin every morning by going out in the garden and reading. Latterly I start with a couple of pages of the Wake and then whatever book I’m reading, currently a light whodunnit by Anthony Horowitz entitled Magpie Murders, easy reading for hard times. When I go to read the second book I find that for a while I’m still in a different reading mode, hyperalert for word play, connections, double meanings; somehow floating a bit above the text; inhabiting a strangely comic world – or is it a comically strange one? That unique reading mode gradually fades but the overlap is interesting and enjoyable. As a linguist, it’s a bit like when you come out of a foreign language, back to English, and the shapes and dynamics of that other language are still what’s shaping your consciousness and thinking.

Picking up from my previous (second) Wake post I’m quickly going to update my lists:

HCE

- Harold or Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker (p30) – see last post

- Howth Castle and Environs (3) = 1st line of the novel, a key location in both the Wake and Ulysses

- Haveth Childers Everywhere (a section published in 1930 as part of Work in Progress) = Adam, father of mankind

- humile, commune and ensectuous (29)

- Here Comes Everybody (32) = Everyman – “for every busy eerie whig’s a bit of a torytale to tell” (20)

- habituels conspicuously emergent (33)

- He’ll Cheat E’erawan (46) = a sinful fella

- haughty, cacuminal, erubescent (55)

- Humpheres Cheops Exarchas (62)

- Haveyou-caught-emerods (63)

- Hyde and Cheek, Edenberry (66)

- House, son of Clod, to come out you jew-beggar to be Executed (70)

- Et Cur Heli! (73)

- at Howth or at Coolock or even at Enniskerry (73)

On Mullingar House pub, Chapelizod, Dublin

Dublin

- Dabblin (p16)

- (Brian) d’ of Linn (17)

- dun blink (17)

- durblin (19)

- Devlin (24)

- Dumbaling (34)

- Poolblack (35) = Dub/black Lin/Pool : dubh linn (Gaelic) black pool

- Dablena Tertia (57)

- Doveland (61)

- Dulyn (64)

- Dubblenn (66)

- deeplinns (76)

- blackpool (85) Blackpool (88)

And I’m starting a third such list- variations on “Ireland”. There is a linkage between HCE and Ireland: HCE > Earwicker > Earlander > Eire > Ireland

Ireland

- Errorland (62)

- Aaarlund (69)

- aleland (88)

(So these are all cumulative lists.)

To round off this post I’d like to start highlighting some of my favourite neologisms and word-collisions. Like the lists above, these highlight the variety and persistence of Joyce’s ludic approach to language. Joyce is “a mixer and wordpainter” as he describes Hyacinth O’Donnell on p.87.

The playfulness and transmutation of language is the essence of the dream state and the act of “sewing a dream together” (28) which is this fluid, complex book. “intermutuomergent” (55) is a wordflow that captures the dynamics of the language of the Wake. This is the “meandertale” (18) to end all meandertales. (The wandering river, the Liffey, runs through that heart of it, personified in ALP. And the neanderthal is just beneath the skin of us hairless apes, we Chimpdens.)

- tellafun book (86) [telephone]

- lexinction of life (83) [lexicon/extinction]

- nekropolitan (80)

- timesported across the yawning (abyss) (56) [transported across time]

- to clapplaud (32) [clap]

BTW my favourite Wake website so far is From Swerve of Shore to Bend of Bay, a blog by Peter Chrisp.

Returning to lockdown, on the basis that the Wake touches on everything, this seems like a good Corona sentence: “the obedience of the citizens elp the ealth of the ole” (76).

The Girl in the Blue Dress

I’m just back from a week in the village of Glencolmcille, Donegal (Ireland) doing a painting class at the Irish college (Oideas Gael). One day there I sat next to a Catweazle-looking fella, an American academic, called Jim Duna in An Chistin (The Kitchen restaurant) and he told me about an artist who had been active locally, a fellow American. At first he couldn’t recall the painter’s name and from the clues he gave I guessed Edward Hopper. It turned out it was one Rockwell Kent. I’m not bad on my art history and that name had never crossed my path.

The next day Oideas Gael put on a screening of an RTÉ documentary from last year about Kent and the subject of his most famous painting, Annie McGinley. After our morning painting session in the village’s National School we traipsed down to the college to watch the film, ‘Searching for Annie’/’Ar Lorg Annie’ by Kevin Magee. Kevin is BBC Northern Ireland’s Investigations Correspondent and it turns out the Gaelic film is actually funded by BBC Gaeilge and Northern Ireland Screen (which I work with often), through their Irish Language Broadcast Fund.

One of the locations used in the film is a room above the better of the two pubs in Glencolmcille, Roarty’s. The next morning, on the way through the village to the hostel (where I was finishing a watercolour of Glen Head [see below] from the vantage point of their cliff-top lounge) I snuck in through an open door and up the stairs of the pub in search of the room as I knew it contained copies of Kent’s paintings. As I walked into the room there sat Jim at his breakfast – turned out he was lodging there. I had a look at the various pictures, poor copies, but nevertheless with some of the power of the originals.

None of Kent’s paintings reside in Ireland. He painted 36 in the Glencolmcille vicinity in in 1926. The most famous and resonant is this one, entitled ‘Annie McGinley’.

‘Annie McGinley’ by Rockwell Kent (1926)

The painting now resides stashed away in a private collection in New York. It should be an icon of Irish painting. This reproduction doesn’t really do it justice. The location remains unchanged to this day. The day after the documentary screening some of the people on the Hill Walking course recreated the pose in the exact spot. The cliff-top is a couple of valleys over from the tranquil, resonant glen of Glencolmcille.

The subject of the painting is the eponymous Annie McGinley, a local girl, about 20, daughter of one of Kent’s local friends. Her father kept Kent’s drying oil paintings in his house as the barn where Kent and his new American wife lived was not dry enough. This is Annie’s father carrying his poitín still away at night to evade the authorities, punningly titled ‘Moonshine’.

‘Moonshine’

The documentary was funny in the way it skirted round the core of the painting. People kept using words like “sensual” and “curvy” when it is clear that the painting revolves around Annie’s bottom. It’s a very sexy image – Kent’s wife would have been right to be concerned. Annie in later life denied even posing for the picture. But as another curvy young woman later said: she would, wouldn’t she.

In my opinion it is the ‘Olympia’ of Ireland.

‘Olympia’ – Edouard Manet (1863)

Someone should make it their mission to get the painting back to Ireland and into the National Gallery in Dublin for all to enjoy. It is as much a part of the national heritage as Paul Henry’s ‘Launching the Currach’ (which sat above the fireplace in my mother-in-law’s good room) and Jack Yeats’ ‘The Liffey Swim’ (subject of my recent Picture of the Month).

‘Launching the Currach’ – Paul Henry (c.1910)

Kent painted a number of pictures during his year in Ireland which could be considered masterpieces. Another one is ‘Dan Ward’s Stack’, men at work during harvest in Glen Lough, an inaccessible valley two north from Glencolmcille, lead by Kent’s friend, Dan Ward (on top, left), neighbours helping like in ‘Witness’ (Peter Weir, 1985, with Harrison Ford).

‘Dan Ward’s Stack’ (1926)

This one ended up not in the USA, to which New Yorker Kent returned after his Donegal sojourn, but in The Hermitage in Moscow. Kent, something of a lefty, was invited to Moscow to be the first contemporary American artist to have a solo show in the Soviet Union. He left 80 canvases to the Russian state after the exhibition, including this one. The Rusky’s loved it for its depiction of collaborative work. Kent’s socialist leanings got him into trouble with the US authorities, got him hauled up in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee under McCarthy (whose mother was from Co. Tipperary), and generally stifled his career. Hence my not having heard of him.

Now my guess of Hopper was not that far wide of the mark. Rockwell Kent was born in June 1882 in New York (of English descent). Edward Hopper was born the next month, July 1982, also in New York. The other painter who came to mind on first seeing Kent’s work was Nicholas Roerich who was born 8 years earlier in St Petersburg, in October 1874. Roerich I first came across in a little museum dedicated to him way up Manhattan island, on W 107th St. The style of Roerich’s landscapes and skies are very reminiscent of Kent – or vice versa. Similar palettes and graphical technique.

‘Path to Shambhala’ – Nicholas Roerich (1933)

‘Monhegan, Maine’ – Nicholas Roerich (1922)

So Roerich was doing very similar landscapes at much the same time.

Interestingly Roerich is described as a “painter, writer, archaeologist, theosophist, philosopher and public figure” – Kent as a “painter, printmaker, illustrator, writer, sailor, adventurer and voyager” – both seem to have been multidimensional characters. Much like Richard Burton, the subject of my last post.

‘Railroad Sunset’ – Edward Hopper (1929)

I’ll have a poke around to see if Kent, Hopper and/or Roerich crossed paths as they were all clearly active throughout the 20s.

It’s not too often I come across a painter as good as Kent out of the blue these days so I feel blessed that Glencolmcille chose to reveal him to me.

Here’s one of the poor copies from the hallway beside the room above Roarty’s

And here’s one from the bar below

Also in the bar below was this photo linking me back to home

On the right is Shane MacGowan, later genius songwriter of The Pogues. He spent his early childhood in Co. Tipperary. On the left is a local from Glencolmcille. Brent Cross is in my manor in London.

Here’s a woman on cliff-top sketch I did my first day in Glencolmcille, before coming across Rockwell Kent

Malin Beg, Donegal

It’s above Tra Ban (Silver Strand) in the next village from GCC. The crouching woman is a fellow painter, Pamela from Eindhoven, Holland, taking a photo with her phone to use back in the studio.

This is my watercolour painting of Glen Head from the hostel vantage point

Glen Head, Glencolmcille

This oil, by Kent, is probably just over that headland

‘Irish Coast, Donegal’ – Rockwell Kent (1926) [The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Russia]

The magic worked on him and it did on me. I found the whole experience meditative. I have never had the opportunity to stay put in one place and paint it over and over from a multitude of angles. The afternoon after completing Glen Head above I went for a walk with two new friends, Micki a muralist and graphic designer from Ohio and Colm a retired economist from Dublin, around the religious sites of Glencolmcille associated with St Colm Cille/Columba, one of the three patron saints of Ireland. As we were walking through the landscape below Glen Head, near the ruins of St Colm’s chapel, I realised I recognised particular rocks and patches of land from having painted them earlier. It was a deep, focused relationship with a place the like of which I haven’t experienced before.

A God’s eye view of Glencolmcille – a watercolour painted with reference to Google Maps on my phone, my last picture of this trip

Picture of the Month: Live & Direct from Dublin

‘The Liffey Swim’ – Jack Yeats 1923

I think this is only the second time I have written a Picture of the Month right in front of the picture itself. The first time was in Buenos Aires in front of a Frida Kahlo self-portrait with monkeys. As I referred to this Jack B. Yeats painting [‘The Liffey Swim’ 1923] in my last post I thought I’d pick up the baton with it, here in the National Gallery of Ireland on Merrion Square, Dublin.

I spent a bit of time yesterday along the Quays and looking at the Liffey, and had a chat with my son about the notion of swimming in this river. He had been watching a documentary about swimming the channel between Scotland and Ireland just before. I mentioned this painting as evidence that people were known to brave the Liffey.

The painting has a real sense of event around it, with spectators filling the bottom left half beneath the strong diagonal that bisects the composition from top left to bottom right. We see a mixed gender crowd (a bare-headed blonde woman prominent near the front) filling the pavement, filling both decks of a bus or tram, filling the bridge and the opposite quay. This is 1923 (or at least painted that year), the first half of which was the time of the Irish Civil War, so to see a crowd united in a joyous occasion must have been resonant.

The image and composition remind me of an early 20th century English painting of an East End music hall (perhaps Sickert? or was it Bomberg?? – I’ll try to find it another time*). And the overall style has something of the Camden Town Group about it – a muddy palette and loose, free brushwork. Yeats was not born in Dublin but in London in 1871, so was 52 at the time of painting this.

The swimmers are swimming crawl in what gives the impression of a strong current. One of the brightest colours is the orange in the part of the water closest to us. The figure nearest to us, a cap-wearing man leaning on the wall to look down into the river, is sliced in half, only his cap, a bit of hair protruding at the back, his neck and shoulder visible, cropped in a photograph-like way.

We can see the face and open mouth of one swimmer as he takes a crawl breath – it has something of Munch’s ‘Skrik’ (Scream) about it though is probably more about the breath of life than anything dark.

No Dublin rain in sight – the skies are blue with some high white clouds.

Apparently this swim was an annual event from 1920. [My brother-in-law Des subsequently informed me that it is still an annual event.] As the War of Independence raged from 1919-1921 at least one, possibly two of these races took place in wartime which indicates life must have gone on during the conflict. It ended in July 1921 so if the race happens in July or later and the one depicted was 1922 not 1923 this would be the first one free from British rule in the capital of a modern sovereign Irish state.

For all I know Yeats may have had little political intent – he was known to be interested in sporting themes (horse-racing etc.) – but I am going to take this as a depiction of joy, hope, energy and freedom.

* It was Bomberg – a painting from the Ben Uri collection, from just three years earlier

‘Ghetto Theatre’ (1920) – David Bomberg, [Ben Uri collection]

The Empathy Podcast with Oisin Lunny

I can’t recall exactly how or when I first met Oisin Lunny – it was through digital media/multiplatform circles. But I do clearly (that is, as clearly as was possible in the circumstances) recall listening to his band in a rowdy basement in Watermint Quay, Hackney on big nights among the London Irish Murphia – they were called Marxman, a pioneering Celtic hip-hop band that used the bodhran, the traditional Irish drum, for their beats. The band was on Gilles Peterson’s Talkin’ Loud label (alongside the great Young Disciples among other footstomping acts which defined the 90s). They had the distinction of having their first single banned by the BBC and their third one performed on Top of the Pops. Oisin making his marx in music is no surprise given his heritage – his da is Donal Lunny, Irish producer extraordinaire and member of seminal bands Planxty and Moving Hearts (with the likes of Christy Moore). Oisin has moved the family on from the bouzouki to all things digital and mobile (but with a healthy respect for the bodhran and the Irish songbook).

Oisin in Marxman (left)

Among his digital marketing related activities Oisin produces a podcast about Empathy called The Empathy Podcast. He recently recorded an episode with me in which we discussed the relationship between Empathy, Creativity, Connection and Networks. Here is the programme [Running Time: 22 mins].

Another Marxman on Simple Pleasures.

Marxman with Sinead O’Connor:

“Ship Ahoy” by Marxman from Oisin Lunny on Vimeo.Omagh – 19 years on

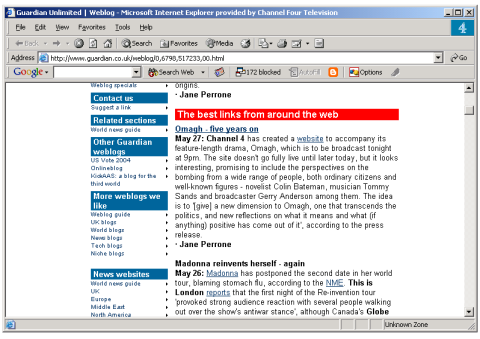

Today is the 19th anniversary of the Omagh bomb outrage. To mark the day I have dug out the copy and materials I gathered with my trusty team for a Channel 4 microsite in 2004 (now long gone) which was created to accompany a drama by Paul Greengrass (who went on to direct the Bourne movies).

The look of the site can be seen here in this archive I made in 2009 on this self-same blog.

Below is the material I am bringing back to light for the record. Each contributor had been asked what Omagh meant to them and whether they see any silver lining in it at all (this was from 5 years after the outrage).

Inbetween I had filmed in the town for Barnardos, a year after the bomb, to highlight the work of child bereavement services. Roddy Gibson and Eddie McCaffrey, then of Emerald Productions, now of Middlesex University, accompanied me on a roadtrip for a location shoot which remains fresh in the mind. I particularly remember being told that there hadn’t yet been a big take-up of adult bereavement services in the wake of Omagh …but people had been coming forward during the year who had been caught up in the Enniskillen bomb. That had been twelve years earlier in 1987.

From the Channel 4 Omagh website (2004)

An item from The Guardian website from the day of transmission, a few hours before the Channel 4 Omagh site went live

The public announcement that followed the broadcast on Channel 4

Omagh Contributions

(Text in bold indicates extracts used or highlighted)

Thanks to the original contributors for their insightful and moving words which I recapture here for posterity.

Seth Linder

Seth Linder is a writer, journalist and campaigner. His books include ‘The Ripper Diary’. He lives in Rostrevor, Co. Down.

Like the assassination of President Kennedy, everyone remembers where they were when they first heard of the Omagh bombing. I was driving with my wife through the Mourne Mountains in County Down, and I think the isolated beauty of our surroundings only heightened the horror of what we were hearing on the car radio. As with the Dublin and Monaghan bombs in the Seventies, it was partly the scale of the tragedy that appalled people but it was also the perception that what was really being targeted was hope. For the first time in thirty years, a peaceful future was a tangible if fragile possibility. Yet, it now seems as though the one consolation to be drawn from the terrible events of that day is that, rather than sabotaging that hope, Omagh led to a greater resolve throughout Northern Ireland to achieve that peace.

For those who lost family or friends or suffered injury and trauma there has been precious little to bring solace over the years. As a journalist, I have interviewed many who have endured similar tragedy, such as those who lost relatives at Hillsborough or Bloody Sunday. Like the Omagh relatives, I am sure, their search for the truth is an essential part of the grieving process.. How can people be expected to finally let go until they feel they have achieved some sense of justice for those they have lost. It took a whitewash and thirty years of campaigning for the Bloody Sunday families to get their public inquiry. The Hillsborough families have not and probably never will receive justice. One could cite many other similar instances. With Omagh we have, yet again, failed as a society to make the one contribution we must make to lessen the burden for those who have suffered so terribly. We have failed to bring them the truth. It is still not too late for the Omagh relatives. I hope this drama helps their cause.

Peter Makem

Peter Makem is a poet and writer from Armagh. His volume of poems Lunar Craving has been described as “some of the finest lyrical verse by any writer since WB Yeats”. Other publications include The Point of Ripeness. He was formerly manager of the Armagh Gaelic football team.

The Omagh bombings are a perfect example of justice for sufferers and victim’s relatives being at the mercy of the many interests and forces that have accumulated over the past thirty five years. These include Secret Service, Special Branch, protection of agents, high legal costs and intimidation. Five years later the impasse is slowly beginning to unblock but only after the relatives themselves have taken vigorous control of their situation. Omagh, the worst atrocity of the entire troubles has most show up the inadequacy of legal redress.

My poem ‘But we were drunk then’ refers to incidents in history when people carry out acts they are later ashamed of and wonder what impulse drove them to it in the first place. The term “drunk” of course does not mean alcohol, but being temporarily carried away by intense ideals, impulses and beliefs. Sometimes when I think of Omagh, I feel I would like to read this poem out to the perpetrators.

But We Were Drunk Then

Cromwell fresh from Wexford town

And the dark set of blood.

Cromwell’s reassembled throng,

Brattle of armour, strike of shod

Return to the camp, line by line

For prayers of thanksgiving,

For hymn and victory song,

And into sleep, and night’s toss- Oh then?

But we were drunk then.

Somebody set us drunk.

Someone slipped drink into our glass.

Only should blinding light come

Would Pizzaro lament the Inca dead,

Or Titus mourn Jerusalem,

Or Herod grip his head in shame.

Only should light strike

Would Paul of Tarsus beg the dark

In skin locked at eyelid

And moan, and curse- Oh then?

But we were drunk then.

Somebody set us drunk.

Someone slipped drink into our glass.

Our piper’s fingers shaped the ancient

Impulse of the race, a first cry

From first born, the story went,

Departing from a lover’s balm

Moved off half soul, half body,

Tossed, twisting storm as calm

And every motion the possession

Of the vanished lover.

Our singers moved around that tune.

Dancers stepped it up the floor.

And dusk is full of beginnings,

High above the fulcrum

Beyond the starling and the plover

Glowing warrior and lover

Soar upon the shores of day

Until their wings fall away.

Only at the still pendulum

Might lips move, whisper pass- Oh then?

But we were drunk then.

Somebody set us drunk.

Someone slipped drink into our glass.

They live on Paradise, they

Moving under long oppression

Bring their flower in full blossom

Before the arc of dawn.

Rendered old, rendered young with pain

Stand attention to their dream,

And all that is not of Eden

Hated in the oppressor’s way

All who should feed the root

Of the forbidden fruit,

And war it is. War the call.

The tidal surge won’t turn

Until its moon is spent.

Prayers floats there, supplication

On the shore bound swell

And rock and great rock shaken.

After, the seas, the shrunken, penitent

Seas far out lap remorse- Oh then?

But we were drunk then.

Somebody set us drunk.

Someone slipped drink into our glass.

reproduced with permission from Peter Makem. (c) 2002 Peter Makem

Katrina Battisti

Katrina Battisti is a theatre nurse from Omagh. She was in Omagh town centre at the time of the bomb.

Both myself and my husband, Shane, are from Omagh and were in town on the day of the bombing. We were trying to park the car and were redirected to another car park because of the bomb scare. On the way we stopped for forty seconds or so to let some cars pass. If we hadn’t, we probably would have been in the vicinity of the bomb when it went off as we were walking in that direction. People were screaming and shouting for help but there was so little you could do. I remember holding paper towels against a girl’s wounds to stem the bleeding. People got organised very quickly, Soon after, that girl was taken to hospital in a furniture delivery van. Our immediate worry was Shane’s sister, Eileen, who has a hairdressing salon opposite where the bomb went off. As we walked towards the salon we saw clouds of smoke, people were staggering around covered in blood, dazed and scared, and there was a terrible smell of burning flesh. I saw a body underneath the mangled wreckage of a car, though I could see no legs.

Eileen had not been injured by the bomb but the panic had brought on a severe asthma attack and we drove her to hospital, where I had actually been working until the day before. The Out Patients area had been turned into a mini treatment room. Cleaners were washing the blood from the floor and you could hear the noise of helicopters taking people away to other hospitals. Lots of off-duty staff and GPs had come in to help. I remember being told that one person had died and one person lost their legs and I was horrified even then. It was a while before we knew the full scale of the fatalities. Despite the shock, the hospital was well organised. Senior staff were taking details of patients and posting them on the noticeboards so relatives knew which ward to go to.

Omagh is a small town. If you don’t know someone, you know of them, so most people knew someone who had lost a member of their family. I just remember when we came home lying down on the sofa, and the impact of what had happened, all the horror, anger and grief we had witnessed, hitting me. I couldn’t sleep for a week and couldn’t get it out of my head for many months. It’s taken a long time for the town to recover physically and psychologically. It’s good to see some of the smaller shops which were destroyed coming back. We now have a two year-old daughter and a baby on the way. We can’t help thinking sometimes of that forty seconds or so we waited for cars and what might have been.

I think the one thing you can take away from that day is the way people rallied around and did all they could to help. There was a real community spirit and there is great admiration for the way the relatives have fought for justice. People like Michael Gallagher. They could have been overcome with hatred and bitterness but they have conducted themselves with such dignity. What people in Omagh can’t understand is what the bombers thought they could achieve. Omagh is a mixed town but it wasn’t a divided town before the bombing and it certainly isn’t now. If anything it has brought people even closer together.

Nell McCafferty

Nell McCafferty is a journalist, broadcaster and playwright – one of the most provocative, interesting activists and commentators in Ireland. She has written for publications ranging from the The Irish Times to Hot Press. Her books include ‘A Woman to Blame’, ‘Goodnight Sisters’, ‘Nell on the North: War, Peace and the People’ and ‘Peggy Deery’. She was born on Derry’s Bogside and now lives in Dublin.

We were on the first night of our holidays in Kerry when the news came in. The northerners separated immediately into a miserable group. The television reception was grainy. Next morning, I went to Mass for the first time since childhood. The priest spoke in Irish, and prayed for the dead of Omagh. Afterwards, in the mist, locals confirmed that we had heard the numbers correctly. Trying to put a face on the little town, I thought of Stevie Mc Kenna, who used to entertain us in the Queen’s University Glee Club with his rendition of a Russian dance. Phil Coulter was his pal, then , in the hope-filled sixties. I do not believe that the bombers meant to kill civilians but their carelessness was morally criminal. It gets on my nerves that the families want to pursue and hold individuals to blame, when all our energies should be directed towards resurrecting the peace process – and the contradiction of that is that I am still clanking my Bloody Sunday chains. So a small part of me cheers for the Omagh survivors who refuse to let any of us forget.

Gerry Anderson

Gerry Anderson is a radio and TV broadcaster. He has a daily show on BBC Radio Foyle/Radio Ulster.

Having lived in Omagh for short periods over the years, I developed a sense of the people who lived there. They were and are articulate, convivial and musical people. And, in a sense, people well accustomed to being passed over and ignored by governments that had consistently failed them. Consequently, no place less deserved the tragedy that befell them.

I was in Omagh a few days after this terrible event when thousands gathered to hear, among others, Juliet Turner bravely communicate with the people through music. It summed up for me the spirit of the people. No other town in Ireland would have permitted a young girl to stand up and sing what amounted to a modern/pop song on such a day.

Shoppers were killed at random but it is no accident that many of their relatives were so capable of graphically articulating their feelings and had the spirit to fight doggedly through the years to ensure that those who planned and planted the bomb would pay for their crimes.

These were ordinary people who rose above themselves. This is the ultimate legacy of Omagh; that ordinary people couldn’t and wouldn’t rest until justice was seen to be done.

Eddie McCaffrey

Eddie McCaffrey is a video producer/director from Omagh.

When asked how they should be portrayed in a ‘promotional’ video, a

year after the Omagh bomb, the people of Omagh overwhelming told me

“tell the world we are ordinary, normal people”. Remaining true to

their own core belief, after all that they have been through over the

last 5 or 6 years, is testimony to the ‘extra-ordinary’ qualities of the

people of Omagh.

Tommy Sands

Tommy Sands is a singer, songwriter and social activist from Co. Down. Pete Seeger said of him: “Tommy Sands has achieved that difficult but wonderful balance between knowing and loving the traditions of his home and being concerned with the future of the whole world.” His songs have been recorded by Joan Baez, Dolores Keane, The Dubliners among many others. His recordings include To Shorten the Winter.

The fifteenth of August was the day we used to go to Warrenpoint to say prayers and paddle in the water. There was a cure that day, they said.

But I was in Milwaukee when the word came through.

Just about to go on stage. It was a festive event with ten thousand in the audience. They had just heard the news too. No one felt like singing yet we knew there was no other way to express such sorrow. Eileen Ivers played a lament on the fiddle. Like a keening song of old, not to make us sad but to let the sorrow out. To bring back life. There was a silence I had never heard before. I sang “There were Roses and the tears of the people ran together”.

Omagh was a defining moment. If there had been any doubts before that we needed to support a peace process there was none now. The last straw. Out of the ashes came a prayerful permanence. Never again. Out of death came a thousand lives suddenly saved. The cure of innocence bestowed upon us all by Omagh Martyrs.

Geraldine McCrory

Geraldine McCrory works for Barnardo’s in Omagh providing bereavement support for children and young people.

I feel that my personal reflections for 2004 are

centred on the fact that in the latter twelve months

Omagh has finally come to life again with lots of

regeneration of the main shopping area. The town

now has a ‘buzz’ about it and this in itself creates,

in my view a feeling of ‘hope’ and ‘trust’ which had

been lost to the town and its community for quite some

time.

I attribute this not only to the Bomb in Omagh but to

the aftermath in which the town, for almost three and

half years, had been subjected to regular bomb hoaxes.

These had the ability to make the town and community

come to a stand still and made us revisit the horrors

of the Bomb in August ’99- whether we wanted too or

not!

For me I see the cessation of these hoax calls as a

‘light at the end of the tunnel’. It affords the

opportunity for the town of Omagh and its local

community to begin taking baby steps towards progress

and moving from Fear and Darkness into Optimism and

Hope!

Dina Shiloh

Dina Shiloh is a journalist. She lived in Israel for 15 years.

In “The Diameter of the Bomb” Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai wrote of the way one bomb kills and injures a specific number of people – those who happened to be a few centimetres from the explosion – and how the bomb’s ripples of pain spread further and are felt by people all over the world. Amichai was writing of the conflict in his city, Jerusalem, but his words are equally resonant for the people of Omagh. The effects of a bomb are not only felt by the families of those who happened to be there at that precise moment, but by their friends, their work-mates, the wider community. Nearly six years after the Omagh events, people in Ireland are still feeling the repercussions of the bomb, yet they have been able to move towards a peaceful resolution of their conflict. Perhaps they can give hope to those in Amichai’s city, Jerusalem.

Colin Bateman

Colin Bateman is a novelist and writer. For a number of years he was the deputy editor of the County Down Spectator. As a journalist he received a Northern Ireland Press Award for his weekly satirical column and a Journalist’s Fellowship to Oxford University for his reports from Uganda. His novels include ‘Divorcing Jack’, ‘Turbulent Priests’, ‘Chapter and Verse’ and ‘Driving Big Davie’. He lives in his native Co. Down.

Omagh was a horrible, horrible thing – but as the years go by, unless you were personally involved, it just gets added to the list of horrible atrocities that went before it. I don`t think there was any `silver lining` or any shift in public perception, there will always be mad bastards who want to kill innocent people to make a point. I kind of like the idea of the killers` children asking, `What did you do in the war, daddy?` I`d like to hear that explanation.

Some Late Arrivals (which did make it to the site)

Eoin McNamee

Eoin McNamee is a novelist and poet. He was born in Kilkeel, Co. Down in 1961. He was educated in various schools in the North and at Trinity College, Dublin. Eoin has lived in Dublin, London and New York. His publications include The Last of Deeds, Resurrection Man, (made made into a feature film for which he also wrote the script), The Language of Birds, Blue Tango and The Ultras.

Eoin now lives in Sligo.

From: eoin mcnamee

Sent: 25 May 2004 14:19

To: Adam Gee

Subject: Re: Omagh – 5 Years On

Dear Adam

try this-its a bit more than 5 or 6 sentences, but they`re short sentences-give me a ring if theres any problem-home til about 4 then on

mobile

best

eoin

Ps marie is shy

The correspondances between the Omagh bomb and the Dublin/Monaghan bombings are striking, five years after one, thirty years

after the other.

These were mass killings of profound political effect, and, certainly in the case of the latter, political intent. The relatives and dead are

in each case alloted their role and refused any other. They face official indifference, incompetence and worse. There is a sense of other

agendas being pursued. What is particularly striking is the way that both sets of relatives have been forced to adopt unconventional

legal tactics to force conclusions-in one case, the inquest process, in the other the adoption of private prosecutions.

The parapolitical complexities which have dogged the North roll on, seemingly immune to change. There is no such thing as the

agendaless dead, it seems, when it comes to the north eastern corner of the archipegelo. We`re told to accept the future as bright, and

history as being a cortege from which we are to avert our eyes. Don`t enquire because you might find out the truth. And that would be the real catastrophe.

Brian Kennedy

Brian Kennedy is a singer and songwriter, a great ambassador of music for Ireland. He was born in 1966 and brought up on the Falls Road, Belfast. His recordings include Live in Belfast, On Song, Get On With Your Short Life and Won’t You Take Me Home. Brian performed in Omagh on 22nd May 2004 and wrote his contribution to this website the following day.

Sent: 23 May 2004 17:24

To: Adam Gee

Subject: OMAGH….a few words from Brian Kennedy.

Hey Adam, just played Omagh last night and it was a WILD show! My goodness,

it was great to see them in such fine form.

So here goes.

” It filled my heart to the brim to hear the people of Omagh sing again

after having so much to cry about. Singing seems to be a different kind of

crying altogether and although Omagh can never be the same again, their

voices rose with a mighty passion known only to those who have lost so much

and lived to see another hopeful day. I felt truly humble in the presence of

these people.”

Love Brian Kennedy.

x

Jeremy Hardy

Jeremy Hardy is a comedian and campaigner.

Omagh was such a sad, stupid, pointless atrocity, committed by people refusing to look at another way forward.

It was an attack on a largely harmonious town – a town which stands as a symbol for what Northern Ireland could be like.

It’s also time that people who want to investigate what happened look not only at the perpetrators but also at the failure of the RUC.

Eamon Hardy

Eamon Hardy is a Senior Producer at BBC Television. He has been involved with numerous landmark documentaries on Panorama and elsewhere including ‘Death on the Rock’, ‘A Licence to Murder’ and ‘Who Bombed Omagh?’ Eamon grew up in Kilkeel, Co. Down.

As a documentary film maker I’ve traveled the world to record some very painful stories, the human scars of war, famine and conflict; the 13 year old girl gang-raped by soldiers in Bosnia, the Palestinian mother who’d just lost her children in an Israeli missile attack. Of all the grief I’ve been witness to however, nothing has moved me more than the stories of the families in Omagh.

I was born and raised in the North of Ireland and still considered it home. I felt an instant and intimate understanding of these people’s lives. Michael Gallagher was a man I knew although we’d never met. His gentle, soft-spoken courtesy as he invited John Ware and myself into his home was that of family friends and relatives I grown up around.

His hospitality too, gallons of well brewed tea and plates of thickly buttered barnbrack, was the taste of celebrations and even wakes from my own childhood. The familiar comfort of his ‘good’ room with it’s china cabinet filled with Belleek pottery and Tyrone crystal could have been my mother’s.

My heart was disadvantaged even before this dignified man told the story of how, after the bombing, he went to search for his son Aiden. He found him. In the mortuary.

Kevin Skelton’s wife Philomena was caught by the blast as she sifted though the rails of a clothes shop. He found her face down in the rubble.

The Skeltons weren’t well-to-do people but were remarkable for their ordinariness and decency. Kevin described with such love a quiet but energetic woman, always on the go. Her sounds were the sounds of his life.

I’ll never forget the haunting description of his loneliness and grief. “It’s an awful thing”, he told us, “to walk into your home for the first time and hear the clock ticking.” For a long time after recording Kevin I heard that clock’s lonely echo.

Oran Docherty pleaded with his mother Bernie to allow him to go on a bus trip to Tyrone. He was only eight and had never been away on his own before. Bernie was reluctant but conceded in the end, as mothers do. After kissing him goodbye she stood at the door of her Donegal home to watch him disappear excitedly down the street. He hardly dared to look back incase his mum changed her mind.

The next time Bernie saw her son was in the mortuary at Omagh general hospital. Her description of seeing him in that moment wrenched the heart of every parent: “Whatever way his wee lip was, his bottom lip, to me it looked as if he was crying when he died”.

I’ve always considered it a privilege to come into these distraught people’s lives and give voice to their grief. I’ve often felt guilt. When the camera stops rolling and the lights go out our strange, fleeting acquaintance ends. We leave them alone with their broken hearts.

Adrian Dunbar

Adrian Dunbar is a film, television and theatre actor and producer. He grew up in Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh. His screen credits include ‘Hear My Song’, ‘My Left Foot’, ‘The Crying Game’, ‘Star Wars: The Phantom Menace’ and ‘The General’. He is currently appearing at the Abbey Theatre, Dublin in The Shaughraun.

I got into a cab in Finsbury Park in London. The taxi driver, who was Irish and knew me, said: “that’s terrible what’s after happening in Omagh.”

What?

“Massive explosion. They’re saying a lot of people dead.”

I couldn’t wait for him to get me home. I got quickly to the phone. Two of my sisters, Roisín and Christina, and their families lived in Omagh.

“They are all ok,” said my mother “and so are Liam and John.”

I didn’t know it but my two brothers were also working in the town that day.

Two weeks later, my wife Anna and I visited Omagh. The shock in the town was still palpable. I looked into the river Strule and remembered as a boy how excited I was when told of the Swan mussels that lived there, and because the Strule was sandy, they sometimes contain pearls. I remember buying my first guitar, a Fender Jazz Bass, from Aidan McGuigan and the fun I had with Frank Chisholm and Ray Moore and Paddy Owens, on the road with Frank’s Elvis show.

Omagh was west of the Bann, overlooked, high unemployment, screwed by the planners, and now this. I said a prayer for the dead and for the living. A couple of months later I was at a party in Omagh. Without warning, a girl broke down in tears. No one rushed to her, a couple of her friends dealt with her calmly. “She was in the bomb” I heard someone saying and that was all.

Like those scary adults of my childhood who had never recovered from the horror of the First World War, old men who would shout and cower in the street, I could see that the people of Omagh would live every day with this tragedy.

May love find them wherever they are.

The homepage of the Channel 4 Omagh website

The design by Mark Limb

A letter to Seamus Heaney

Seamus Heaney

X Strand Road

Sandymount

Dublin 4

Eire

23/04/2004

Dear Seamus

I am currently working on a project which I thought may be of interest to you (I was involved in the ‘Omagh: Where Hope & History Rhyme’ video made for the District Council a few years ago to which you so kindly contributed) and wanted to invite you to express your reflections on Omagh from five years on.

As you may know, Channel 4 has commissioned and now taken delivery of a drama on the bombing of Omagh and its aftermath (written by Paul Greengrass) and as part of the on-line programme support (on the channel4.com website) we are adding a reflective dimension to the project by including the thoughts of various people connected with Omagh and Northern Ireland in a variety of ways (not straight-forwardly political, mainly cultural) about what Omagh means to them from the perspective of 2004 and what (if any) silver lining they can see to this cloud.

The easiest way to contribute your thoughts would be by sending them in by email to agee@channel4.co.uk.

Otherwise we can speak on the phone and you can dictate your comments. Or of course a good old-fashioned letter to: Adam Gee, Channel 4 – 4Learning, 124 Horseferry Road, London SW1P 2TX.

It would also be very helpful to get a photo/image to illustrate your contribution. Do you have an image of yourself, a book cover or something related to you which we could use for this? (Ideally an image you own the copyright in and are happy for us to use in this context. If however it belongs to a third party, then could you please also supply details of the copyright owner so we can clear the image properly for usage.)

I do hope you can find the time to share your reflections.

Kind regards

a d a m . g e e

c r e a t i v e / c o m m e r c i a l . d i r e c t o r

c h a n n e l 4 . 4 l e a r n i n g

0 2 0 . 7 3 0 6 . 8 3 0 6

0 7 7 8 7 . 5 0 1 1 4 8

agee@channel4.co.uk

http://www.channel4.com

Selections from the Channel 4 Omagh forum

every person should watch this as an education for our futures !!!!

i cant even begin to say how much that film has touched me. i remember the bomb happening, but i was only 11 so i dont really remember much about it. however, my heart goes out to all the families and victims of the omagh bombing. its events like this that make u realise life is precious, and you should treasure every moment

The integrity of Michael Gallager and all the Support Group members is a lesson to us all and an inspiration in a country where no doubt many other appalling deals have yet to come to light. Sensitively handled and superbly dramatised.

A magnificently made documentary, with superb low-key performances, sensitively portrayal of the events, and cleverly incorporation of all victims. I am 22 years old and in such a short life, I have seen many tragedies in my life. I also grew up in Ireland and after a while one gets used to it… Why should I get used to it?

this is exactly the sort of programme the BBC should be producing instead of gardening make overs and eastenders. well done channel 4.

Possibly the best piece of television to be aired in the UK in the last 10 years(or more). Brilliant in every aspect.The realism of the bombings and the grief process.The casting, the editing.especially the direction and camera work…..outstanding. Well written and punching their message home.

Six years now since I walked into my sitting room and flicked on “Sky News” to hear “Broken things ” being sung so poignantly at their commemoration service. Ten years this July since I buried my own dear son Sean.

Well done Channel 4….Well done

Thank you for being brave enough to make this programme. It is one of the best I have ever seen. I can’t see to type properly for my tears.

To all of you involved…..my thanks. To the families involved….I know you will never forget, or forgive but I hope that every day you feel a little better than the last, you are ordinary special people and a wider audience are listening tonight.

hello, i am 16 and have lived in omagh all my life. even though i was only young when the bomb happened, i can still remember it as if it was yesterday, things like that you will never forget, i have so much sympathy but also respect for anyone who was involed in the helping out during the bombing, sympathy for what they had to go through and the tragedy they had to experiance and respect for their courage. that day is a day i will remember always, it has left a scar in the hearts of many many people and no matter how much people get on with their lives, there will always be reminders. the people of omagh have grown stronger because of this tragedy. and hopefully all the families of the victims can get on with living their lives to the best they can. May peace stay with them and strength to move on.

Reading this board it seems to me that this drama on Channel 4 tonight has made a lot of people think. I hope it isn’t the triumph of hope over reality to hope that it’s made the right people, on both sides of the divide, think?

It seems that too much goes on behind our backs with the governments and political parties/groups and its the innocent who suffer from it

I can only agree with all the commendation for this excellent program. It stands as a chilling reminder of the the kind of priorities which rule the peace process though.

there was no good of any kind that came out of this terrorist act, nor the policing that was supposed to be there to stop it.

i left ni not long after this and unfortunatly those who initially seemed to be doing good for its future are back doing no good in other ways.

This was a very well produced programme which brought back many painful memories to me. I just hope that it can help remind those who hold NI’s future what they are there to do. They seem to need reminding.

Can C4 send every idiot polition in NI a copy of this for their collection and name it ‘never forget why!’.

I found it very moving and very well done.Well done C4,RTE,Irish film board.I only hope yesterdays ruling in Belfast about the real ira not being a terrorist group under the terrorism act does not affect the families court case against the RIRA.We need more TV like this.

As an ex RUC member the drama refuels the anger felt towards the ombudsman. The Nationalist political points scoring from Nuala Oloan.

Ask any Policeman how good an informer is, at the bottom of it he is a criminal, a liar and out to get money. The information from Fulton was crap, there is absolutely no doubt in that.

If Police were to act on all information, no one would go to work.

Ask the Ombudsman;

1/ how many threats came in regarding a second bomb in Omagh for several weeks after August 98?

2/ How many threats are there regarding threats to life in Northern Ireland right now in 2004?

Its an easy target the Police, not so easy doing the job, nobody wants to help and there are many double edged swords and pitfalls along the way.

My thoughts go out to the families concerned, they like many thousands in Northern Ireland will never get Justice. Those involved in the many crimes against innocent people over our history will be judged by their creator.

To the ex RUC gentleman. Few of us from the North who have any sence don’t know the excellent job the force does in protecting the people of Northern Ireland and the program cant have shown the individual act of RUC men in Omagh in 1998 that were so important in preserving the lives of those who survived.

Still I am sure you understand how difficult the lack of transparency must have been to the families involved.

Those families will be an inspiration to us all in the years to come thanks to programs of this kind. Scotsmen play films such as Braveheart to give them pride in their heritage but all Northern Irish people can be proud of the commitment of those families.

I was a member of the organisation that has been the subject of so much criticism in this programe. Indeed I was on duty that terrible day. Not at the time of the explosion but several hours after. We were brought in to search the damaged buildings for the injured or the dead. Most of the buildings were near to collapse. We risked everything to enter those buildings in the vain hope of finding people alive. We then spent the next five days digging through the rubble in the bomb scene trying to find evidence, to piece together the the device, in order to catch the perpetrators of this terrible crime. Unfortunately I don’t believe that I’ll ever recover from the experience.

Despite the contents of this programe, I know that we did our level best during those days to do what had to be done to bring those responsible to justice.

My thoughts are with those left behind.

The program has shown the RUC to be criticised at it’s leadership and intelligence level. Lets not confuse that with the many men and women of the service who worked so hard at that time. I saw a police officer crying that day. What those people had to deal with was awful, but they did it with dignity and great inner strength. Many of those officers are suffering to this day. I am sure that some must blame themselves for leading so many people to that end of town. I dont think any of us blame thos officers for anything. Those officers who were there that day are as much victims as the ordinary members of the public. They too were let down. Lets not forget that they too are people like the rest of us.

I feel that if anything positive is to come of this programme it will be to remind those not living in Ulster that no one has ever been brought to justice for this atrocity and that just because we don’t hear about it in the news anymore it doesn’t mean that the suffering has stopped.

i also have lived in omagh all my life it is a beautiful town and there is not a day goes by that we suffer in silence about that awful day the fear of finding our loved ones dead and the guilt that we felt for finding them alive no film can ever show what we suffered and will continue suffering in silence no matter who is found quilty , if ever found quilty

I moved to Omagh from England shortly before the bomb, and was thankfully not allowed into the town that day as the police were in the process of setting up the cordon. I heard the bomb go off a few minutes later and my first reaction was of disbelief and confusion. I didn’t want to believe what was clearly obvious.

I watched the program this evening and found myself reliving aspects of that day and the months that followed. Thankyou for a necessary reminder of a day that should never be repeated and never never forgotten.

In the months that followed, I found on my trips back to England that everyone I came into contact with knew of Omagh. At the time I thought it a shame that Omagh was so well known for such an appauling reason, but I now find that when I speak to people on the phone from England, or when I visit England, everyone I meet appears to have never heard of Omagh. I have asked people “Do you not remember the bomb?” I find that they dont.

I actually find this far more disturbing than I would ever have imagined. That something so terrible can happen and capture the attention of so many people around the world and then be forgotten in so few years is a poor reflection of the world in which we live. We must remember so that we can learn. Forgetting the past to move forward to me is absurd.

Thanks again to the program makers for a necessary wake up call.

I’m from Omagh but moved to England in 1999. There’s not a single day that goes by that I don’t think of everyone at home. There are often tears. It was incredibly difficult to watch this programme tonight but I felt that Gerard McSorley, a native of Omagh, was excellent.

The question is, what can we do to help?

I would just like to say thank you to channel 4 and most of all the families of Omagh bombing for bringing this tragady more into the pubilc eye with a moving and heart felt documentary.

I am also disgraced in the way that the families were treated by the so called justice system.

Please let me know what actions we can take to help you fight for what is right.

Well done to channel 4 etc for highlighting the ongoing heartache of Omagh. I realise that with something so horrendous, much needs to be censored, but I was there, and the scenes from this program don’t even begin to show the true extent of the suffering. The hospital scenes in particular only showed the tip of the iceberg.

It was much much worse than that.

I had my reservations about watching this. I didn’t spend the last 5 and a half years trying to get those memories out of my head just to have them all brought back, but I was really impressed by the sensitivity shown by the film makers. This was painful, but compulsive viewing.

This was a well written, well researched peice. Well done channel 4.

As a grown man i don’t think i have cried in a long time, but watching that last night just made me very emotional. I’m not from Omagh and don’t for one second pretend to feel the same as those families but i was sadden and sickened.

I have never felt so emotional about any piece of drama.

Well done Channel 4 for making such a touching and thought provoking film. It can’t have been easy.

I have nothing but admiration and respect for the victims’ families, who retained their dignity and courage whilst coming up time and again against those who just wanted to ignore them for the sake of the peace process. In my view, there can be no peace until they are heard and the lessons are learnt.

Adam and the eve

Yesterday in 1916 was supposed to be the day of the Easter Rising in Ireland. However, because Eoin MacNeill countermanded the order, the rebellion was delayed by a day amid confusion. I marked the eve of this momentous event in Irish history with a day in Dublin of much more coherence.

It began at the GPO in O’Connell Street, epicentre of the Rising, with a visit (with my sister- and brother-in-law) to a new permanent exhibition space built into the yard of the Post Office as part of the centenary commemorations. The exhibit I most enjoyed seeing was one of the original printed posters of the Proclamation. Due to a shortage of type in Liberty Hall where the document was printed on the eve of the insurrection the C in Republic is made from a converted O and the E in the next line (“to the People of Ireland”) is made from an F with an extra bit added in wax.

At the end of the exhibition is a marble and digital wall of all the recognised 1916 combatants (all those eligible to receive a pension from the State) on which we found my wife’s great uncle Patrick Donnelly of Louth, something for my two half-Irish boys to take pride in.

We walked up O’Connell Street with various signs of the centenary commemorations in windows and on lampposts, portraits of the Proclamation signatories, banners from the city council. The Sinn Fein office had a suitably Soviet hoarding with raised fist heroics. We ducked into Moore Street, to which the GPO combatants fled at the end of the uprising, visiting the lane where the O’Rahilly had died after writing a haunting last note to his wife (one my late sister-in-law Bronagh used to have on her wall). We also saw the houses/shops where the fleeing revolutionaries took shelter, numbers 16-20, which are currently under threat from property developers. In front of the boarded up red brick buildings was a rough looking band of Northerners from some kind of pipe band, tattooed to the hilt.

This set us up nicely for our next encounter – masked (Continuity) IRA men at the Gardens of Remembrance (which are dedicated to the memory of “all those who gave their lives in the cause of Irish Freedom”) gathering for a parade to the GPO. Those not in paramilitary-style masks and shades had on Celtic shirts with player names on their backs like Pearse and Sands. This motley crew looked out of step with the times and as bonkers as the rebels may well have seemed as they left Liberty Hall for the GPO on Easter Monday 2016.

We popped in to the Hugh Lane (Dublin City gallery) for a fascinating exhibition about Roger Casement, High Treason based around a large painting of Casement’s appeal by John Lavery, High Treason: The Appeal of Roger Casement, The Court of Criminal Appeal, 17 and 18 July 1916.

From there the three of us headed over to Glasnevin cemetery, the only location in Joyce’s Ulysses I’d not yet visited, and the main burial place in Ireland. From Michael Collins’ much-decorated grave to De Valera’s down-at-heel one, from monumental sculpture by James Pearse (father of Patrick and Willy) to the small marker for Countess Markievicz (part of a mass Republican grave), we followed a super-enthusiastic (oddly) Dutch historical guide around a 1916 themed tour under bright afternoon sunshine. The various characters joined by the Glasnevin tour also linked back to both the Casement case and the many stories making up the content of the new GPO exhibition. So all in all it was a considerably more coherent day than 23rd April 1916 in Dublin and across the country, and more satisfying.

High Treason: The Appeal of Roger Casement

100 years on to the minute and the yard

It’s strange how things work out. I found myself today at noon under the portico of the GPO in Dublin, by my calculation within a couple of feet of where Patrick Pearse first read the Proclamation of Independence 100 years ago today. I’ve no Irish blood but I find the event very meaningful and resonant and it meant a lot to me to be present there and then. I made a special trip to Dublin for today to mark the centenary of the Easter Rising.

I took the train in to Connolly Station (named after one of the signatories of the Proclamation, socialist leader James Connolly, in 1966 to mark the 50th anniversary) from Rush, a small station north along the coast from Dublin where scenes of Neil Jordan’s Michael Collins were filmed. On the train I sat at a table with a mother and daughter who were busy planning the logistics of some major shopping manoeuvres for the day. I revelled in the gap between what was on their mind and what was on mine.

On arrival in the city I walked round the corner to Liberty Hall, Connolly’s headquarters which played a central role in the planning of the uprising. The original building from which the rebels marched to the GPO on the fateful day is no more – in the Sixties it was built over to make a statement about modernity in the form of a highrise union HQ. Shortly after I arrived a woman dressed in dark green 1916 Irish Citizen Army uniform was preparing (with a modern worker with a droopy moustache and hi-viz vest) to raise an Irish flag of the era. She was then joined by two other ICA women and a troop of armed men dressed up in period uniforms. They marched out of an adjacent alley and gave the flag-raising sufficient gravity before a crowd of just a couple of dozen motley passers-by, tourists and left-leaning supporters.

I followed them off along the quay to the point where they were dismissed and wandered off. As I walked down the quay on the route I imagine the rebels took just before noon on 24th April 1916 to the GPO in Sackville (O’Connell) Street I could easily conjour up their emotions – they would have been perhaps slightly self-conscious in similar ‘unofficial’ uniforms as they walked among the few Easter holidayers on the streets that Monday morning. They would have been nervous on the short walk knowing they were about to raid the GPO and reach a point of no return.

As I turned right into O’Connell Street a crowd was gathered in front of the GPO. A trade unionist or socialist of some kind was making a speech, amplified off a stage just beyond the General Post Office, recounting and interpreting the events of Easter Monday 1916. Banners for various contemporary campaigns to do with energy companies and water charging and the like leant an appropriately grass-roots political vibe to the gathering. This was the Citizens’ Commemoration and it was a refreshing contrast to the bigwigs’ official ceremony on Easter Monday a few weeks ago. Suddenly on stage appeared a friend, ironically from just the other side of Highgate Hill from me, actor Adie Dunbar, who was playing Master of Ceremonies with his usual aplomb. I texted him from between the bullet-scarred classical columns of the Post Office. As noon approached, the hour Pearse came out of the building to give the Proclamation its first airing to mainly uninterested passers-by, somewhat against the odds I saw the mother and daughter from the train. They were rushing by through the now dense crowd with shopping bags in hand, pretty much oblivious of the commemorative event going on around them – a perfect echo of the Dublin citizens who largely ignored Pearse and his men.

A few minutes before twelve Adie announced that a descendent of one of the GPO combatants, the O’Rahilly, would lay a wreath at the entrance to the monumental building. Proinsias O’Rathaille, the grandson, walked a few inches in front of me and I found myself among a small group of media photographers as he laid the wreath to the fallen. As the clock above the window in which the emblematic black sculpture of Cuchulainn is displayed struck noon I was within a couple of yards of the focal point. Strangely I don’t think anyone had focused on the precise spot where Pearse would have been standing.

Foggy Dew was sung. The Proclamation was read. The Soldiers’ Song was sung. I watched for a few more minutes from the stone base of a column. I left to the strains of Fenian Women’s Blues, a song by a young Irish singer drawing attention back to the women who participated in the Rising but were to a large degree airbrushed out of history.

I walked round the corner to the Winding Stair bookshop, one of my favourite spots in Dublin, and picked up a souvenir in the form of a copy of Ruth Dudley Edwards’ new book The Seven, about the signatories of the Proclamation. Still buzzing from the intersection of history, time, place, my life – the rhyming of hope and history.

History says, Don’t hope

On this side of the grave,

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed-for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up

And hope and history rhyme.

My Patrick Pearse T got another outing today

Today in 1916, Dublin – Easter Tuesday – Support real and imagined

Easter Tuesday (25th April 1916)

British troops (and machine guns) on the streets of Dublin

Holed up in the GPO Padraig Pearse writes an optimistic report for a Republican newssheet: “The Republican forces everywhere are fighting with splendid gallantry. The populace of Dublin are plainly with the Republic, and the officers and men are everywhere cheered as they march through the streets.” Not totally true. At the Jacob’s factory, for example, a mob jeers at the Volunteers inside: “Come out to France and fight, you lot of so-and-so slackers!” (I suspect they didn’t really say “so-and-so”, the feckers.) Pearse also writes a Manifesto to the Citizens of Dublin: “The country is rising to Dublin’s call and the final achievement of Ireland’s freedom is now, with God’s help, only a matter of days…” Not totally true. Risings outside the capital are to a large extent sporadic and confused.

British troops marching prisoners

Rumours abound. The Germans have landed in support of the uprising. Rebel reinforcements are converging on the capital. Cork has fallen to the Volunteers. The British barracks are beseiged and on the point of surrender. The whole country is up in arms. Not true at all.

In fact British troops are arriving in numbers by train overnight from Belfast and Kildare and en route by sea from Britain. They machine gun the men and women of the Citizen Army on St Stephen’s Green, firing down from the height of the Shelbourne Hotel, forcing them to retreat to the College of Surgeons. They take back the City Hall, confusing the female rebel fighters for kidnap victims. “Did they do anything to you? Were they kind to you?”

They retake the Daily Express offices beside City Hall. Meanwhile in the Irish Times (paper not building) reports of the uprising are suppressed and replaced by a short piece of under 50 words, opening…

Yesterday morning an insurrectionary rising took place in the City of Dublin.

and a counter-proclamation from Lord Wimborne, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, announcing the imposition of martial law. The authorities are getting a grip on the situation after a slow start. The proclamation speaks of “a reckless, though small, body of men” and of “certain evilly disposed persons”.

Next: I’ll pick up Easter Wednesday (26th April 1916) on 26th April 2016

Today in 1916, Dublin – Easter Monday – One small step, one giant leap

Easter Monday (24th April 1916)

Padraig Pearse

Around noon James Connolly and Padraig Pearse lead 150 rebels up Dublin’s O’Connell Street. They march as far as (appropriately enough) the Imperial Hotel when Connolly suddenly gives the order to wheel left and charge the GPO. Once inside the first task was to persuade baffled customers that they were for real and that said customers needed to take off, get outta here.

Pearse had been appointed President of the Republic and it fell to him to proclaim said republic. He came out of the Post Office looking “very pale” and read the now famous proclamation.

Liguist and writer Stephen McKenna was among the small crowd who witnessed the momentous event:

Liguist and writer Stephen McKenna was among the small crowd who witnessed the momentous event:

“For once, his magnetism had left him; the response was chilling; a few thin, perfunctory cheers, no direct hostility just then, but no enthusiasm whatever.”

Half an hour later a company of mounted British lancers charge down O’Connell Street, sabres drawn. Shots ring out from the GPO and the Imperial Hotel, killing four of the imperialists and scattering the rest. Battle has commenced.

Rewind to the start of this resonant day. Rebels turn out in Dublin but in reduced numbers after the chaos of Easter Sunday. They gather in the guise of Irish Volunteers on manoeuvres but at noon transform into determined and bold revolutionaries. They seize key buildings across the city with the GPO as HQ – Boland’s Mill, Jacob’s Factory, the South Dublin Union and other strategic buildings. The Citizen Army takes a position on St Stephen’s Green. (During the night British troops sneak into the overlooking Shelbourne Hotel effectively neutralising the position.)

They move on Dublin Castle, the centre of British administration, but misjudge and hesitate resulting in the gates being shut in their faces. They take adjacent City Hall instead. During the aborted assault Abbey actor Sean Connolly shoots an unarmed police constable, making 45 year old James O’Brien one of the first fatalities of the Rising. A couple of hours later, at 2pm, Connolly, up on the roof of City Hall, takes a bullet in the stomach and bleeds out in front of his 15 year old brother, Matt.

Looting starts around O’Connell Street as local people sense the opportunity of disruption.

More lofty deeds are being carried out on the roof of the overlooking GPO. Eamon Bulfin, a lieutenant in the Irish Volunteers, is sent up to raise a green flag with the words Irish Republic and a golden harp.

made by Mary Shannon, a shirtmaker in the cooperative at Liberty Hall

A green, white and gold tricolour is also raised on that roof, for the very first time over the Republic of Ireland.

The largest military parade in the history of the Irish state passes the GPO as part of the 1916 Easter Rising centenary commemorations in Dublin – 27 March 2016

The essence of Padraig Pearse

Today in 1916, Dublin – Easter Sunday – A bit of a mess

Easter Sunday (23rd April 1916)

Marked the day by going to the National Film Theatre to see The Trial of Sir Roger Casement, a television play from 1960 (on Granada) starring Peter Wyngarde as Roger Casement, who was hanged for treason 100 years ago not a million miles from here (in Pentonville prison) and even more shamefully chucked into a pit of lime. That’s Peter Wyngarde of Jason King and Department S fame. It was 56 minutes of skilfully crafted court room drama, with a contemporary commentary well integrated into the flow. Casement was arrested on Good Friday 100 years ago…

Scroll forward two days and it is as much a confused fiasco as Casement’s bumbling efforts on the Kerry coast. Had the arms shipment from Germany brokered by Casement arrived as intended, Eoin MacNeill, Chief of Staff of the Irish Volunteers, might have supported the Easter Rising but as it was, considering the rebels to be underarmed and to have no chance of victory, he countermands the order to gather and ultimately rise up against the English and thereby creates confusion across the country. The plan had been to assemble armed men (and women) of the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army across Ireland as cover for the start of the Easter Rising.

MacNeill’s withdrawal of the order for ‘manoeuvres’, indeed “all orders given to Irish Volunteers for tomorrow, Easter Sunday”, is published in the Sunday Independent.

The Countermand Order

Significant numbers of IV and ICA gather in Dublin and across the country but are uncertain what’s to happen. Needless to say it’s raining in much of the country as the volunteers hang around awaiting orders. Most end up dispersing (although many are still set to mobilise the next day if so commanded).

The rebel leaders decide just to postpone the uprising until Easter Monday despite MacNeill’s countermanding order.

Eamonn Ceannt

Eamonn Ceannt, one of the seven men to sign the Proclamation of Independence which was read out today (2016) in front of the GPO in Dublin, as it is every year on Easter Sunday, was on the IRB (Irish Republican Brotherhood) Military Council with Joseph Plunkett and Sean MacDiarmada. He was appointed Director of Communications as well as commandant of the 4th Battalion of the Volunteers. During the Rising his battalion of over 100 men was stationed at the South Dublin Union, with Cathal Brugha as his second-in-command.

Ceannt returns home at 2am on Sunday and tells his wife Aine: “MacNeill has ruined us – he has stopped the Rising.” In the morning he heads to Liberty Hall to consult with Connolly and the others. His battalion meanwhile gathers at his house, the bicycles stacked four deep in the front garden. Ceannt returns to the house in the evening and begins filling out mobilisation orders. The bundle of papers commands his men to assemble again on Easter Monday. The decision to proceed is in motion…

Once the GPO fell and the rebels surrendered, Ceannt, like the other leaders, found himself in Kilmainham Gaol. He was shot like the rest in the stonebreaking yard on 8th May. He was 34. He wrote a last message a few hours before in cell 88:

I leave for the guidance of other Irish Revolutionaries who may tread the path which I have trod this advice, never to treat with the enemy, never to surrender at his mercy, but to fight to a finish… Ireland has shown she is a nation. This generation can claim to have raised sons as brave as any that went before. And in the years to come Ireland will honour those who risked all for her honour at Easter 1916.

Today (2016) the Irish tricolour was raised above the roof of the GPO with planes of the Irish Air Force flying overhead trailing green, white and orange. What would Ceannt have made of that?

The ceremony in the Stonebreakers’ yard in Kilmainham Gaol today with The President of Ireland and the flag of the state

The ceremony in our kitchen today with the flag of the state

Leave a comment

Leave a comment