Archive for the ‘Picture of the Month’ Category

Picture of the Month: Live & Direct from Dublin

‘The Liffey Swim’ – Jack Yeats 1923

I think this is only the second time I have written a Picture of the Month right in front of the picture itself. The first time was in Buenos Aires in front of a Frida Kahlo self-portrait with monkeys. As I referred to this Jack B. Yeats painting [‘The Liffey Swim’ 1923] in my last post I thought I’d pick up the baton with it, here in the National Gallery of Ireland on Merrion Square, Dublin.

I spent a bit of time yesterday along the Quays and looking at the Liffey, and had a chat with my son about the notion of swimming in this river. He had been watching a documentary about swimming the channel between Scotland and Ireland just before. I mentioned this painting as evidence that people were known to brave the Liffey.

The painting has a real sense of event around it, with spectators filling the bottom left half beneath the strong diagonal that bisects the composition from top left to bottom right. We see a mixed gender crowd (a bare-headed blonde woman prominent near the front) filling the pavement, filling both decks of a bus or tram, filling the bridge and the opposite quay. This is 1923 (or at least painted that year), the first half of which was the time of the Irish Civil War, so to see a crowd united in a joyous occasion must have been resonant.

The image and composition remind me of an early 20th century English painting of an East End music hall (perhaps Sickert? or was it Bomberg?? – I’ll try to find it another time*). And the overall style has something of the Camden Town Group about it – a muddy palette and loose, free brushwork. Yeats was not born in Dublin but in London in 1871, so was 52 at the time of painting this.

The swimmers are swimming crawl in what gives the impression of a strong current. One of the brightest colours is the orange in the part of the water closest to us. The figure nearest to us, a cap-wearing man leaning on the wall to look down into the river, is sliced in half, only his cap, a bit of hair protruding at the back, his neck and shoulder visible, cropped in a photograph-like way.

We can see the face and open mouth of one swimmer as he takes a crawl breath – it has something of Munch’s ‘Skrik’ (Scream) about it though is probably more about the breath of life than anything dark.

No Dublin rain in sight – the skies are blue with some high white clouds.

Apparently this swim was an annual event from 1920. [My brother-in-law Des subsequently informed me that it is still an annual event.] As the War of Independence raged from 1919-1921 at least one, possibly two of these races took place in wartime which indicates life must have gone on during the conflict. It ended in July 1921 so if the race happens in July or later and the one depicted was 1922 not 1923 this would be the first one free from British rule in the capital of a modern sovereign Irish state.

For all I know Yeats may have had little political intent – he was known to be interested in sporting themes (horse-racing etc.) – but I am going to take this as a depiction of joy, hope, energy and freedom.

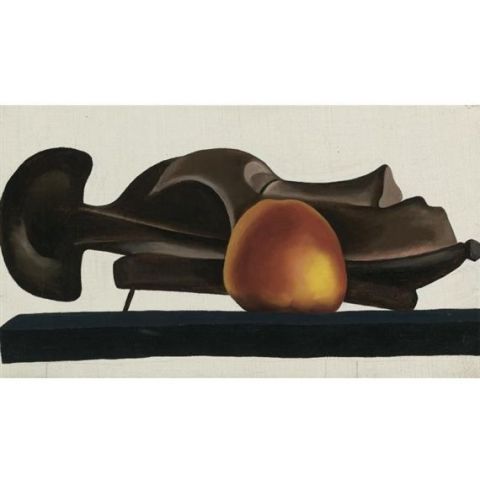

* It was Bomberg – a painting from the Ben Uri collection, from just three years earlier

‘Ghetto Theatre’ (1920) – David Bomberg, [Ben Uri collection]

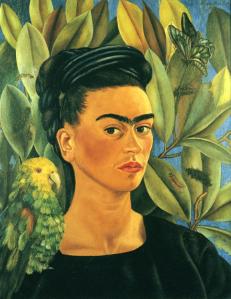

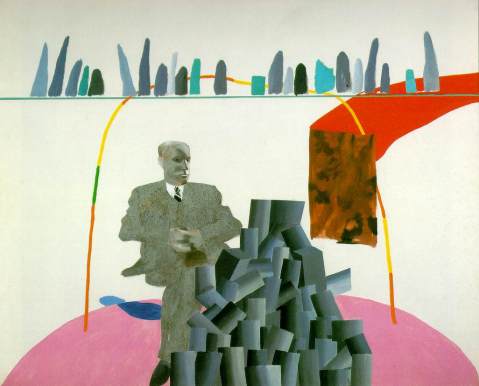

Artistic Devices: Hockney in London 2017

I was working at Chelsea School of Art in Pimlico recently and took the opportunity, after a meeting about a prospective TV programme, to nick into Tate Britain which is directly opposite and see the David Hockney exhibition.

To mark the occasion of this major retrospective, entertaining if a little rammed, I’d like to dig out my Hockney Picture of the Month, Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices, which is in the show of course.

Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices (1965)

And to add an extra something to celebrate the exhibition I’d like to highlight some other artistic devices in evidence in this show. For the significance of ‘artistic devices’ I’ll quote from my earlier post:

The person portrayed is partly obscured by a pile of (obviously painted) cylinders. Above his head is a shelf on which are a selection of large brushstrokes. The cylinders are crude 3D representations, obvious devices or techniques, which stand out as abstract in a still figurative world of suits and rugs and shelves. The shelf is just a 2D line. The strokes on the shelf are more flat, abstract components of painting, exposing the technique and undermining the illusion. The pile of cylinders is actually painted on a sheet of paper glued to the canvas to leave the viewer in no doubt as to the artifice, physical materiality and flatness of the endeavour.

Sunbather (1964) – water devices (although it’s complicated – Hockney had painted lines on his pool floor)

A Bigger Splash (1967) – plant devices & more water devices

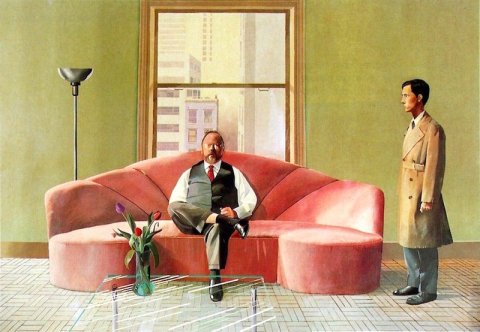

Henry Geldzahler and Christopher Scott (1969) – glass devices

Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy (1970-1) – carpet devices

Marilynne Marilyn – Picture of the Month: The Only Blonde in the World by Pauline Boty (1963)

The Only Blonde in the World (1963) by Pauline Boty 1938-1966

My mum is called Marilynne Marilyn. Not a lot of people know that. My grandfather couldn’t spell the name, got it wrong on the birth certificate, wasn’t allowed to cross it out, so had to have a second go. Marilynne Marilyn is a blonde.

Today I have been reading about Mandy Rice-Davies of Profumo Affair notoriety. Another blonde in the world. Her real first name was actually Marilyn. Not a lot of people know that.

Marilyn Monroe, as the biggest star in the world and the epitome of late 50s female sexuality (at least as far as men were concerned), was a popular subject for Pop artists on both sides of the water.

Marilyn Diptych (1962) by Andy Warhol 1928-1987

Monroe died (or was hounded to her death, as Boty might say – she considered Marilyn “betrayed”) in August 1962 from an overdose of barbiturates. Warhol spent the rest of ’62 creating images of her, all derived from a publicity photo for Niagara (1953). The right-hand half of the diptych speaks of fading and mortality.

Monroe died at just 36. Boty only made it to 28.

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) by Peter Blake

Marilyn features on the centre line of one of the most famous of all Pop images, the one that was actually just a millimetre or two from the pop itself (in the form of black vinyl). She’s just above Ringo and Johnny Weissmuller, swamped in a sea of men.

‘Randy Mandy’ wrote of her bubbly blonde public image: “Every man’s sexual fantasy – it’s a curious role to play in life. I meet men who were schoolboys when my picture was front page news and they greet me as a figment of an erotic dream. There is nothing I can do about this, it has nothing to do with the real me. That Mandy is a pert blonde who is all things to all men. Perhaps that is her secret – she never disappoints.”

Marilyn aka Mandy exiting the infamous trial of Stephen Ward (1963)

The big David Hockney exhibition opens at Tate Britain in a few hours, a retrospective of 60 years of painting. The Hockney generation at the Royal College of Art (at which I’ve been privileged to be working recently, under Neville Brody, Dean of the School of Communication) lusted to a man (bar presumably Hockney himself) after Boty who was every inch the attractive blonde.

Pauline Boty

in BBC Monitor ‘Pop Goes the Easel’ directed by Ken Russell

1963 emulating Hockney’s muse

The blonde in Boty’s painting is far from the only one in the world. The title is ironic. It’s Marilyn. It’s Pauline. It’s Mandy. It’s Diana. It’s any number of fantasy blondes.

Michael Winner directs Diana Dors (28th January 1963)

In ‘The Only Blonde in the World’ Marilyn is contained within a flat, abstract space – both the left and right green panels are higher than Marilyn’s panel. The designs of that space have echoes of Sonia Delaunay’s Orphism which was shown in London around this time.

Sonia Delaunay 1942

The 2D green abstract panels slide open to reveal a glimpse of a ‘3D’ space in which Marilyn positively buzzes with energy. Her famous legs are descendants of Marcel Duchamp’s celebrated Nu descendant un escalier n° 2 (1912).

Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2 (1912) by Marcel Duchamp

I’m not sure where Boty’s Marilyn image is drawn from. Some critics and commentators say Some Like It Hot but I can’t find any such image – I think it may be from the premiere of The Seven Year Itch. It doesn’t really matter where exactly it came from, the point is I’m pretty sure there will be a specific photo out there that she used as a source, one in a magazine, to align with the popular culture focus of British and American Pop Art.

Marilyn and Joe DiMaggio at the premiere of ‘The Seven Year Itch’ (1955)

The vibrating energy of Boty’s Marilyn reflects her genuine admiration of Monroe as a woman mythologised through pop culture. The grey background, which links out to the lines and swirls of the abstract framing image, picks white Marilyn out like a spotlight at a Hollywood premiere. She’s a flash of white brilliance as she crosses the gap. The journey between the two green panels is short but Marilyn still steals the show, as she did in her tragically short life.

Little did Boty know but her own would also be cut tragically short. They found cancer when she went for the first scan of her first child. The brevity of her life has left her to a large extent written out of British art history. ‘The Only Blonde in the World’ is the only Boty in the Tate. Otherwise the only British public gallery holding a Boty is Wolverhampton Art Gallery. The bulk of her paintings languished for many years in a barn. She was an exact contemporary of Hockney (born the year after him). She went to the Big Studio in the sky just three years after capturing’The Only Blonde in the World’. Had she lived and had time to evolve I wonder whether it might have been her massive retrospective opening at Tate Britain tomorrow…

Celia Birtwell and some of her heroes (1963) by Pauline Boty 1938 – 1966

(That’s a young Hockney bottom right having a smoke.)

Celia Birtwell by David Hockney

Hockney in his Notting Hill flat with his friend and muse, textile designer Celia Birtwell (1969)

Birtwell with Hockney in front of his ‘Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy’ (2006)

(Birtwell was married to fashion designer Ossie Clark)

Hockney with Birtwell in ‘A Bigger Splash’, directed by my first boss, Jack Hazan (1973)

Related posts:

The last Picture of Month – also touching on the Profumo Affair

An earlier Picture of the Month featuring a young Hockney at the RCA

A recent Profumo walk related to Mandy aka Marilyn Rice-Davies

Chairman of the Board – Picture of the Month: Christine Keeler by Lewis Morley (1963)

The other day I got to touch this chair…

The Keeler chair

The year I was born this chair got to touch the bare bottom of Christine Keeler.

photograph by Lewis Morley

It was as the scandal of the Profumo Affair was exploding in Britain, marking the end of the age of austerity and heralding the new age of permissiveness.

I’ve been writing a script over the summer in which Keeler appears as a minor character so have been immersed in the era of which this photograph is an icon.

The photo session was in Lewis Morley’s studio above The Establishment Club in Soho (18 Greek Street) which was the spiritual home of the emerging anti-establishment of the early 60s. It was founded in 1961 and presented among others, on the small stage on the floor below Morley’s studio, Lenny Bruce, Barry Humphries and Dudley Moore. The club was part-owned by Moore’s partner in crime Peter Cook, another defining character of the era.

Lewis Morley (1925-2013)

Morley was born in Hong Kong to English and Chinese parents, coming to England straight after the war in 1945. He eventually emigrated to Barry Humphries’/Dame Edna Everage’s native Australia in 1971.

Dame Edna by Lewis Morley (1996)

The Keeler session was set up to produce images for a film that never happened (The Keeler Affair). Present were Morley, his assistant and the producers.

I recently came across another such movie that was never made featuring Keeler’s partner in crime Mandy Rice Davies. Her picture, by contrast in costume, was shot by Terence Donovan (1936 – 1996), another of the key photographers of the Blow Up generation. His first major retrospective – Speed of Light at the Photographers Gallery, London this summer – brought to light this magazine cover:

Morley decided to use one of a number of chairs he’d recently bought at (probably) Heals as a prop. They are cheap knock-offs of a classic Arne Jacobsen design, the 3107. The chair is more crudely made than its original and has a hand-hole introduced to get round copyright infringement.

The actual Keeler chair

The 3107 v The Keeler knock-off

At the beginning of the session Keeler was dressed in a leather jerkin, covered (just) but still plenty sexy. Morley shot three rolls of film on the day – on the first two he shot her dressed in this way both on and beside the chair.

Keeler had been a model in her early years in London before getting sucked in to The Scandal. She had also been a showgirl and good-time girl, all these activities and aspirations adjacent in England in the late 50s/early 60s.

The producers then demanded that she pose nude. They insisted that was in her contract. Morley was reluctant and protected Keeler, both with the back of that chair and by clearing everyone but himself out of the studio and averting his eyes while she stripped off and mounted the chair. In this way he protected her dignity whilst fulfilling the terms of the contract.

He then shot the third roll. He tried various angles which you can see on the contact sheet which now lives at the V&A. Morley recounted the end of the session thus:

“I felt that I had shot enough and took a couple of paces back. Looking up I saw what appeared to be a perfect positioning. I released the shutter one more time, in fact, it was the last exposure on the roll of film. Looking at the contact sheet, one can see that this image is smaller than the rest because I had stepped back. It was this pose that became the first published and most used image. The nude session had taken less than five minutes to complete.”

Last shot of the last roll – suitably mythic.

The shot in question can currently be seen in the first room of the You Say You Want a Revolution? Records and Rebels 1966-1970 exhibition at the V&A. As can the chair.

What’s powerful about the shot is the X-shaped composition made up of her upper arms and thighs, bright in the high contrast, combined with the echo of the top half of that white X (those upper arms joined into a curvaceous triangle by her shoulders) which matches the sensual curved triangle of the chair back. The hands and wrists also make up a mini X, reinforcing the power of the central shape. The dark V of the chair back is a massive amplification of that hidden famous vagina. But topping off the shot is an alluring yet refined face. And a strong one, as challenging as any of the enigmatic eye-to-eye starers of Manet. [see E for Enigma – Manet Picture of the Month]

Morley used the pose again two years later with Joe Orton, the playwright who best captured the essence of the 60s in Britain. I first came across Orton in the Lower 6th (the freest and best year of school) when I was looking for the subject of a project and came across Orton by chance. I’ve loved him since. But I don’t find that the Morley portrait captures him well as it gives no sense of his cheekiness or humour.

Joe Orton 1965

Morley also used the pose with TV personality David Frost (in the same year as Keeler), but in a less still way, capturing something of the energy which was to land Frost a chair opposite President Nixon in the next decade (in the famous 1977 interviews which did for the leader of the most powerful nation on earth). Frost, The Establishment, Cook, Private Eye were all part of the same Swinging Sixties circles.

David Frost 1963

Circles which overlapped with the establishment with a small e and their interface with Soho, pretty girls, gambling dens, sharp-suited gangsters, swinger parties, all the ingredients in the explosive brew that was Profumo.

Christine (21) & Mandy (18) at the height of the Profumo Affair

For a very particular moment – arguably one key frame – Morley managed to transform a 21 year old (who grew up in a converted railway carriage, abandoned by her father), a 21 year old swirling helplessly in a maelstrom of post-war British politics, the Cold War and the breaking down of the class system into a strong and dignified woman, the epitome of Sixties British beauty.

Under The Chair

Whole in a Hole – Picture of the Month: Pelvis 1 by Georgia O’Keeffe (1944)

Pelvis 1 – Georgia O’Keeffe (1944)

Reviewing Georgia O’Keeffe’s life’s work at the extensive exhibition currently showing at Tate Modern, it is clearly a journey of abstracting Nature to capture and communicate its essence.

The journey as portrayed in this retrospective has the following landmarks along the way: early experiments with pure abstraction, exploring synaesthesia and detached from figurative representation; taking the figurative edge off of cityscapes of New York; immersion in Nature in New York State; flower paintings; discovering New Mexico; bone paintings and New Mexican landscapes; last works including aerial landscapes. I pick out Pelvis 1 as the culmination of the journey.

It is the brilliant realisation that you can create a ready-made abstract of Nature through the simple device of a dried bone from the arid landscape of New Mexico. O’Keeffe used the hole in a pelvis bone to frame the brilliant blue of the Southern sky. In so doing we have both the figurative representation of a piece of sun-bleached bone and patches of sun-drenched sky; and a two-colour abstract centred on a big blue ball. There’s just enough shadow on the bone and shading in the sky to retain the literal representation of the scene and yet the execution is simple enough to read as a Modernist work of Abstract Expressionism.

The tightly cropped presentation owes something to the art of photography – O’Keeffe was married for over two decades to the photographer and modern art promoter Alfred Stieglitz.

The degree of abstraction is amplified when we consider the date: 1944. There was some heavy shit going on for the USA in ’44 and even more so for humanity and the world and yet we have here purity and tranquility. Having said that, over half of the picture area is made up of Dead Stuff (bone). Pelvis can be read as a momento mori, a meditation on the finite life of Man and Nature’s creatures in contrast to the infinity of the heavens.

O’Keeffe was consciously in search of what she termed “The Great American Thing”, a form of art as native and characteristic as, say, Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby was in terms of the novel. That other Great American and lover of Nature, Henry David Thoreau, swore by Simplicity:

Our life is frittered away by detail. Simplify, simplify.

Mask with Golden Apple – Georgia O’Keeffe (1923)

And our own apple-lover Isaac Newton captured it well:

Nature is pleased with simplicity.

So is Art.

Another great American Modernist, architect Frank Lloyd Wright, (much influenced by Thoreau) summed it up as well as anyone:

Simplicity and repose are the qualities that measure the true value of any work of art.

By those measures Pelvis 1 is a masterpiece. I love it for having boiled down the essence of the Human Condition (mortality in the face of eternity) like the desert strips the rotting body down to pure white bone. O’Keeffe collected bones from 1929, initially due to Nature holding back its bounty: “That first summer I spent in New Mexico I was a little surprised that there were so few flowers. There was no rain so the flowers didn’t come. Bones were easy to find so I began collecting bones.” She began painting them from around 1931, initially mainly skulls. She painted them as still lifes; superimposed on landscapes in the Surrealist manner; integrated into the landscape sitting in the foreground. That this painting features the pelvis rather than the skull I also love because this is not about brains and thinking, this is about cohones and feeling, about instinct and the deepest-down understanding.

Georgia O’Keeffe by Alfred Stieglitz

* * * *

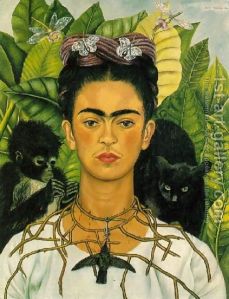

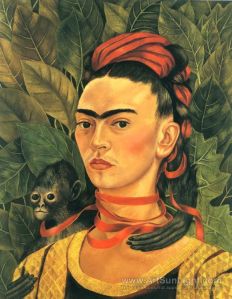

A previous Latino Picture of the Month: Autorretrato con Chango y Loro (Self-portrait with Monkey and Parrot) – Frida Kahlo (1942)

Picture of the Month: He Came He Soared He Conquered – Rosewall by Peter Lanyon

Rosewall – Peter Lanyon (1960)

As we approach the new year it feels like a good moment to reflect on changing perspectives. ‘Rosewall’ is the first of Peter Lanyon’s gliding paintings. Born in St Ives at the end of the Great War and central to the St Ives Group during the 50s, he took up gliding in 1959, inspired in part by observing the flight of seabirds over his native Cornish landscape, the subject at the heart of his painting. This painting was completed in January 1960, four months after Lanyon started his glider training. Before taking up the glider, he was keen on dramatic high perspectives like cliff edges and hilltops. Rosewall is a hill in Cornwall.

So ‘Rosewall’ was his first work to benefit directly by this new aerial perspective. We are used to the sky sitting blue at the top of the landscape but here it is what frames the whole experience. And the experience is a vortex of air, light and wind. Swirls of white air between us and the green grass and brown earth.

I’m not big on totally abstract painting – I prefer the kind with vestiges of the figurative – grass, earth, sky, clouds, the components of landscape, but combined with the feelings it provokes – vertiginous spectacle, thrill and fear, soaring freedom. Abstract expressionism of a rooted kind. While its head is in the clouds its feet are on the ground. At once airy and earthy.

Lanyon explained his motivation for gliding: “…I do gliding myself to get actually into the air itself; and get a further sense of depth and space into yourself, as it were into your own body, and then carry it through into a painting.” He linked his practice at this time to Turner and saw himself as part of a core English tradition of landscape painting. I love the notion of making possible for yourself a physical expereince so you can subsequently capture it in paint.

For the first time ever a comprehensive collection of Lanyon’s gliding paintings is now on show – in an exhibition at the Courtauld Gallery in Somerset House, London (running until 17th January 2016). Filling just two rooms, it’s a small but perfectly formed show, well worth catching to experience the ambitious scale of the artworks. This 6′ x 5′ painting normally resides in Belfast in the Ulster Museum.

Lanyon was taught by Victor Pasmore at the Euston Road School and Ben Nicholson in Cornwall. Nicholson was a contemporary at the Slade of Paul Nash whose aerial paintings like Battle of Britain (1941) would seem to be not-so-distant cousins of the Gliding Paintings. I love the landscapes of Nash for their combination of modernity and deep-rooted tradition, as much in the spirit of European Surrealism as in the heritage of English Romanticism. Lanyon is a worthy successor and deserves to be better known.

Peter Lanyon in his glider (1964)

***

Previous Pictures of the Month.

Pictures of the Month

Autorretrato con Chango y Loro (Self-portrait with Monkey and Parrot) – Frida Kahlo

Skrik (Scream) – Edvard Munck

Joie de Vivre – Picasso

Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices – David Hockney

Merry-Go-Round – Mark Gertler

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère – Edouard Manet

Picture of the Month: Autorretrato con Chango y Loro (Self-portrait with Monkey and Parrot) – Frida Kahlo (1942)

I’ve never written a Picture of the Month in situ before but it’s a rainy Spring afternoon in Buenos Aires and I feel so inspired by this painting in the Malba gallery that I feel compelled to get a bit of energy out of the system. I’m dedicating this one to Una who would love this painting.

What’s unusual is that in many ways it’s a very simple painting, not much to work with – the artist, a monkey, a parrot and a background of wheat. Usually I pick images with more complexity to focus on in Picture of the Month.

I’m about 20 inches away from it now, phone in hand to jot this on.

The eyes (woman, monkey, bird) make an equilateral triangle which is the heart of the composition. Frida’s look slightly left like she doesn’t give a monkey’s about the viewer. Her lips are tight. Her cheeks red. There’s a bit of anger or disdain or probably defiance there.

The parrot looks straight out with both of its side-mounted eyes looking directly at the viewer – the only one of the three doing so. I saw a green parrot like this yesterday up in the trees at the bird sanctuary across town by the port, the Costanera Sur ecological reserve at Puerto Madero. Incongruously some distant relatives, also bright green, hang out occasionally in the allotments beside my house.

The monkey is looking out of the frame to the artist’s left – only one black eye visible like a Jack of spades.

Frida’s hairband is green and yellow like the parrot. Her hair is black like the monkey. She is integrated with them. Are they two aspects of her? Talking and thinking or feeling? Her parents? Her children? Two people she knows? Two aspects of Mexico? No clues really – maybe they are just two animals or familiars.

The parrot sits on her shoulder. Not much sense of its weight. The yellow and maroon dress she is wearing is flat and unruffled, making the parrot not quite of this world.

The monkey is embracing her, an arm behind her back and one on her shoulder. They look close whoever he/she is. It’s got a little quiff. Its face is at once baby-like and old, more the latter.

His (why do I keep thinking it’s a male?) fur links to her amazing gull-shaped monobrow through the shared colour and her unflinchingly portrayed moustache. She has black eye-liner echoing those eyebrows. The lip hair reflects them. So some strong X-shaped geometry is the focus of her face.

The background of wheat reminds me of Van Gogh. The yellow is related to his sunflowers. The tendrils at the top suggest growth and something of the jungle. The shapes also remind me of Rousseau’s vegetation.

…on reflection, I don’t think it’s wheat. I think it’s some kind of exotic jungle plant. So we’re in a Latin-American jungle world albeit of a light and limited kind, no sense of enclosure by trees.

After 20 minutes standing here what do I take away about this beautiful picture? It’s more for Frida than for us – or at least she’s giving us only so much. The rest is hers.

Here’s the last Picture of the Month – as you can see the series title has a touch of irony about it.

Son of a Beach – Picture of the Month: Joie de Vivre – Picasso (1946)

I’m writing this post on a Mediterranean beach in Greek Cyprus as that is the essence of this painting: Mediterranean light and sensuality, Classical culture, family fun and frolics. It is the beating heart of the Picasso Museum in old Antibes, the single work which captures the spirit of the collection based in a beautiful grand old house overlooking the sparkling sea.

I’m writing this post on a Mediterranean beach in Greek Cyprus as that is the essence of this painting: Mediterranean light and sensuality, Classical culture, family fun and frolics. It is the beating heart of the Picasso Museum in old Antibes, the single work which captures the spirit of the collection based in a beautiful grand old house overlooking the sparkling sea.

The Musee Picasso in the Marais of Paris is a wonderful collection cutting across the great man’s lifetime of work (I consider Picasso alongside Bacon as the greatest of 20th Century artists). This collection is far more specific, capturing a brief period after the war when Picasso was in effect artist in residence on a floor of the Chateau Grimaldi, which in 1966 was renamed the Musee Picasso, Antibes. This month was my third visit – I was hooked by the vibe of the place when I first visited about a decade ago with my other half. I was back again last year when I walked over the hill from Juan Les Pins whilst over for the International Digital Emmys. I was back again for those and a speaking sesh at MIP this year and spent a marvellous Sunday there. As I walked up the hill from the old covered market I coincided with the Palm Sunday congregation exiting the resonant ochre church opposite the museum, carrying a variety of symbolic, palm-related plants including woven crosses of palm. I sat myself down on the stone bench in the square separating the church and the Chateau Grimaldi, a stoney canyon giving on to the sea between high walls and blocks of shadow, and sketched the view from the sail-boats flowing across the waves to the students sitting looking out to them, bathed in the bright Mediterranean light.

Without having done any biographical research, I get the impression Picasso was recharging his batteries here after the war, delighting in the Simple Pleasures, from fish to music, from sea urchins to women in all their complexity, from good food and wine to friendship. The photos beside his studio floor by Michel Sima show him with Francoise Gilot, mother of his children, with Paul Eluard (Surrealist poet) and Nusch Eluard (his wife, Surrealist muse), in local restaurants along this bit of coast, working away in the cool shadows of the top floor of this building in sandals, bare torso, bullish like his Minotaur characters who seem confounded, in the line drawn illustrations on display, by the naked women in their lives and their own hairy nature.

The painting depicts a scene from the Classical age of the Mediterranean. It is part of a process Picasso seems to have been going through to extract the essence of the Classical past for his modernist age, to reinvent it for a world post A-bomb, post-Holocaust, post-Guernica, post-mechanisation and industrialisation, to use it to reconnect with the Simple Pleasures and the world of light.

The scene is centred on the family, with a nuclear family of the average 2 point whatever kids cavorting on the beach. The colours are the muted earth colours of Mediterranean pottery, a not too distant relation of the five earthy colours of ancient Egyptian tomb art which were picked up by Bridget Riley in the late 80s (I was fortunate to attend a lecture by her in Cambridge in about 1986 when she talked through her process of adopting that ancient palette, then I saw them for real in tombs along the Nile to Aswan the following decade).

At the centre of the picture is a woman with big knockers. So far, so Picasso. She’s suitably distorted/multi-angled though well beyond the Cubism – she’s Cubist plus 1920s Classical phase plus a sprinkle of Blue Period, all simplified towards Klee territory. Not only are those big bazookas symmetrical but so are her legs and locks so she is very much the centre line of the composition. To her left are the kids (literally – half goat) and a musician with ancient Greek pipe thingies – again, child-like in Klee style, fat fingers and circle head. To her right is a musical centaur, perhaps the Great Man himself in his combination of animal passion and artistic sensitivity. With his bestial four legs he’s that bit smaller than the woman. But it’s all pretty tension free, music, dancing, Mediterranean fun and frolics at the seaside. Those two vertical halves are divided into thirds horizontally – land / sea / sky – dominated by blues which are the hues of peace and infinity. The earth and ocean are a collagy style of painting, direct descendants of his Cubism. The sky is dominated by a classic sail boat in Vermeer blue and yellow. It’s pretty big in the greater scheme of things and for me represents Picasso’s escape route and back-of-the-mind sense that fun and family, luxury and high life by the Med are all well and good, but he has other stuff to go out and explore…

I’m finishing writing this post a couple of weeks later back in London with a print of Guernica as reimagined by Pure Evil on the wall behind me. As far as that Paphos beach is from this North London suburb, so is this Joie de Vivre from the explosive hell of Guernica – separated by a monstrous war and yet in the forms and techniques, the animal imagery, the faceted design, they are not that far apart. Under a decade separates the two (9 years) – by road 9 hours or 900 kilometres (an almost straight line through San Sebastian, Bayonne, Toulouse, Montpelier, Nimes, Cannes; a gently undulating line like the horizon of the ocean in the painting). The son of a beach would really have had the feeling that time heals all wounds.

Previous Picture of the Month: Portrait surrounded by Artistic Devices – David Hockney (a huge Picasso fan)

Picture of the Month – Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices

Exactly a week on from the Oscars triumph of the very English ‘A King’s Speech’, I’ve just been re-watching Colin Firth’s first on-screen stammering in Pat O’Connor’s ‘A Month in the Country‘ (1987) and reveling in the bucolic portrayal of deepest Yorkshire, also a reflection on the art and craft of painting, so my choice this time out is a painting by one of Yorkshire’s greatest sons, David Hockney, and the theme of Hollywood runs through this.

My first job out of college was for film production company Buzzy Enterprises. One of my bosses there was Roger Deakins, pipped to the post last week for the Best Cinematography Oscar by Wally Pfister (for ‘Inception’), Roger’s work on the Coen Bothers’ ‘True Grit’ recently earned him the BAFTA. One of Roger’s partners was Jack Hazan, director of the landmark British cinema verite film ‘A Bigger Splash‘ (1973) featuring Hockney and his circle, including fashion designer Ossie Clark; his wife, textile designer Celia Birtwell; Peter Schlesinger and Henry Geldzahler. The latest user-generated review of it on IMDB is none too flattering but brings me nicely to my picture, Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices (1965). This is what Jaroslaw99 of Michigan makes of the film: “Why was the naked swimmer pressed up to the “window” while two others ate dinner, obvlious? Sometimes I think just because the “critics” or “art aficionadoes” can’t understand art or film, they think it is “deep”. That is what I think of David Hockney (the art was mostly one dimensional like grade school children’s) and the same for this film.”

Portrait Surrounded is very much about dimensions (two and three), representation in art and the border between figurative and abstract painting.

The two things I always liked about Hockney is his profound respect for Picasso (in common with Birtwell whose prints were strongly influenced by Picasso and Matisse) and his cheeky sense of humour. I rank Picasso with Bacon as the two greatest artists of the last century. In this painting the use of the phrase “artistic devices” and their very literal depiction in the painting typify Hockney’s playfulness and deflation of the stuff of “critics or art aficionadoes”.

The person portrayed is partly obscured by a pile of (obviously painted) cylinders. Above his head is a shelf on which are a selection of large brushstrokes. The cylinders are crude 3D representations, obvious devices or techniques, which stand out as abstract in a still figurative world of suits and rugs and shelves. The shelf is just a 2D line. The strokes on the shelf are more flat, abstract components of painting, exposing the technique and undermining the illusion. The pile of cylinders is actually painted on a sheet of paper glued to the canvas to leave the viewer in no doubt as to the artifice, physical materiality and flatness of the endeavour.

Cezanne, one of the fathers of Modernist painting, was keen on the simplification of natural forms into their geometric basics – to “treat nature in terms of the cylinder, the sphere, and the cone” (letter to Emile Bernard 1904). Portrait Surrounded is part of Hockney’s on-going questioning of the received wisdom of Modernist painting in the wake of his spell at the Royal College of Art (with the likes of RB Kitaj) and his struggle to find the right balance between abstraction and figurative art.

The person portrayed in this picture is Hockney’s father and the artist is playing out a battle in it between the technical demands of representing the three dimensions of the physical world and the desire to capture the greater depths of emotion and sentiment, like the feelings one has for one’s parents. In his autobiography Hockney wrote: “the thing Cezanne says about the figure being just a cone, a cylinder and a sphere: well it isn’t. His remark meant something at the time, but we know a figure is really more than that, and more will be read into it… You cannot escape the sentimental – in the best sense of the term – feelings and associations from the figure, from the picture, it’s inescapable. Because Cezanne’s remark is famous – it was thought of as a key attitude in modern art – you’ve got to face it and answer it. My answer, of course, is the remark is not true.”

His observation is typical of the cycle of revolts and reactions of art (as well of teenagehood) – I believe Cezanne was actually referring to landscape not figures so Hockney is actually refuting something created through the Chinese whispers of art education. But that doesn’t really matter, it helps him ‘face and answer’ a key issue for his practice.

In the summer of 1960 the Tate held a large exhibition of Picasso’s work which Hockney visited over half a dozen times and recalls as “a very liberating influence”. He found in it permission for the painter to experiment and move through styles in his artistic journey. Earlier that spring he had visited a one-man Bacon show at London’s Marlborough Gallery. In that he saw a strong stand against pure abstraction whilst retaining an emphasis on directly affecting the guts and nervous system through paint. Bacon’s devices like leaving bare large expanses of canvas to literally expose the workings of painting soon became incorporated in Hockney’s work. His pure abstracts of 1959 (the year he entered the RCA as a post-grad) gave way to the combination of abstract and figurative, and the revealing of the techniques and devices of painting to make clear that painting is not a description of the world perceived through the senses but an interpretation and expression of it in all its complexity, not least of the messiness of emotion. Partly obscured behind the pile of cylinders and partly flattened by his collagey suit, the point of depth of this picture is in the father’s flesh, his Baconesque hands and more still his face and eyes – in fact the two dark points of his eyes, the two one dimensional parts of the painting are the deepest (so Jaroslaw99 of Michigan and I can agree for a moment on the single point of one dimensionality).

In the 3D world I’ve only crossed paths with Hockney fleetingly – both times when reviewing exhibitions in the early 90s, once at the site of that influential Picasso show and the other time round the corner from the Marlborough at the Royal Academy (1995). He projected an attractive combination of Yorkshire homeliness and Californian glamour.

He moved to California the year I was born and in 1965, just after Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices, he made a set of lithographs entitled ‘A Hollywood Collection’. Conceived of as ‘an instant art collection’ for a Hollywood starlet, it includes prints like ‘Picture of a Pointless Abstraction Framed Under Glass’ for which he draws not only the pointless abstraction but the frame and even the reflections on the glass, more playing around with artistic devices in the quest for that sweet spot between the abstract and the figurative where deep feeling and insight reside.

Previous pictures of the month: Mark Gertler / Manet

Comments (2)

Comments (2)