Archive for the ‘apocalypse now’ Category

What is it worth?

We parked up by Goldhawk Road tube (always echoes of Jimmy the Mod for me) and walked back past the Pie, Mash, Liquor and Eel shop to my most unloved venue in London, the Empire in Shepherd’s Bush. Stephen Still’s blast from the past included his underground classic ‘51.5076 0.134352’ and concluded with ‘For What It’s Worth’ which resonated in a particular way after another week of global economic disintegration. What is it worth?

There’s something happening here

[the day before yesterday rounds off a 20% FTSE fall]

What it is ain’t exactly clear

[although I think we’ve all got a good sense of broadly what territory we’re in – how we got there is a bit more confounding]

There’s a man with a gun over there

[currently a cold-hearted woman, life-long member of the NRA: “our leaders, our national leaders, are sending soldiers out on a task that is from God. That’s what we have to make sure that we’re praying for, that there is a plan and that that plan is God’s plan.”]

Telling me I got to beware

[are they really going to elect a man who keeps calling the electorate “my friends” in a manner devoid of warmth or friendship?]

I think it’s time we stop, children, what’s that sound?

Everybody look what’s going down

There’s battle lines being drawn

Nobody’s right if everybody’s wrong

[there’s a real opportunity here, with the merry-go-round ground to a halt, to get off the ride that goes nowhere]

Paranoia strikes deep

Into your life it will creep

[anxiety is seeping out of every opening crack]

It starts when you’re always afraid

[yet fear is what holds us back individually and collectively]

You step out of line, the man come and take you away

We better stop, hey, what’s that sound?

Everybody look what’s going down

Stop, hey, what’s that sound?

Everybody look what’s going down

What’s that sound? It’s mud falling on a coffin lid. It’s ancient song shot through with deepest pain. It’s the sound of a single man burying 20,000 bodies one by one. On Tuesday Rev. Leslie Hardman MBE died. He featured as a key character in a docudrama, The Relief of Belsen, commissioned by Channel 4 which was shown almost a year ago to the day (15.X.07). He was one of the first Allied soldiers (an army chaplain) in to the Bergen-Belsen death camp in North-West Germany when it was liberated in May 1945. Auschwitz had been liberated by the Russians a couple of months of months earlier but it was Belsen that gave us in Britain our first terrifying view of what was going down. This was Richard Dimbleby’s report from the camp…

“Here over an acre of ground lay dead and dying people. You could not see which was which … The living lay with their heads against the corpses and around them moved the awful, ghostly procession of emaciated, aimless people, with nothing to do and with no hope of life, unable to move out of your way, unable to look at the terrible sights around them … Babies had been born here, tiny wizened things that could not live … A mother, driven mad, screamed at a British sentry to give her milk for her child, and thrust the tiny mite into his arms, then ran off, crying terribly. He opened the bundle and found the baby had been dead for days.

This day at Belsen was the most horrible of my life.”

Leslie Hardman was a man who knew what’s worth what. He insisted on burying each of the 20,000 corpses that confronted him as an individual with an individual ceremony (no question of mass burial). He restored in death the dignity they had been denied in life.

In a tribute to him on Radio 4 this morning, a resonant phrase from Kierkegaard (via psychiatrist Viktor Frankl) was cited to capture the man he was : The door to happiness opens outwards. Leslie Hardman dealt with the chaos he experienced in the front-line by dedicating himself to the well-being of others.

As Jonathan Sacks (the Chief Rabbi of the UK) put it on the same radio programme: He Chose Life. Now I always thought – and this was reinforced by the Glasgow office of Channel 4 which has the words engraved on the glass of the entrance – that “Choose Life” comes from FilmFour’s Trainspotting. But apparently it comes from Moses in the Old Testament: ” I place before you today life and prosperity, death and adversity. … Choose life that you and your descendants shall live” (which echoes what his predecessor and my namesake was told: “You may choose for yourself, for it is given to you.”)

Now Jim (the God, not the Mod), much though I respect him, summarised his approach as being to “get his kicks before the whole shithouse goes up”. As things fall apart, I’d say the rock-striking prophet is a better bet than the pose-striking rock god: Choose Life. Choose sustainable living. Choose actually creating something instead of gambling nothing. Choose holding hands not holding hostages. Choose what’s going up. Choose what’s of real worth.

The C Word

Walking into work the other day I was delighted to be confronted by a proper demo. Not just a common or garden demo but a demo by a full-on, fully paid up Cult. The Moonies were outraged by Channel 4’s indelicate portrayal of their romantic mass wedding in My Big Fat Moonie Wedding. I stopped for a minute to talk to a boy who said he was 16 but looked less and asked him why he wasn’t in school – apparently he was on study leave. Yeah, chin Jimmy Hill chin – some people will believe anything …and others won’t. So I trotted up stairs and my colleagues in the immediate vicinity of the pile of papers formerly known as my desk were talking about the demo. Michael Palmer, business affairs man and fellow wearer of Adidas Chile 62s (fast becoming the unofficial uniform of the department), came up with a fabulous definition of religion: Religions are just cults that got lucky.

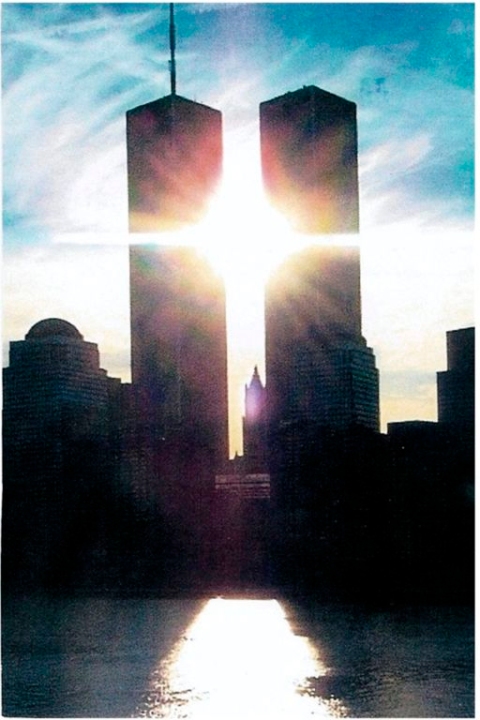

A couple of days earlier I’d gotten back from New York where I was speaking at the World Congress of Science and Factual Producers, presenting the Big Art Project to an international audience of telly-makers. I didn’t get down to Ground Zero (which I’ve never seen, haven’t been in NYC since before 9/11) but I was thinking about it and the absence on the skyline.

Just before I left for Noo Yoik, my very old friend Judyth Greenburgh was back in her native London for a few days sorting out her old pad in Camden Town. She now lives on a houseboat in Sausalito, California where we enjoyed a fabulous holiday stop-over the year before last on our way down Route 101. When Judyth worked at Saatchi & Saatchi, long, long ago before she headed West, her boss was a certain Paul Arden.

Yesterday morning I was at an engaging, lively facilitated discussion session on Blogging. It was chaired by James Cherkoff who I first encountered a couple of years ago at a New Media Knowledge conference at the Royal Society of Arts. Here is his Twitter picked up within moments of the finish by the organisation who’d employed him:

“I’ve just moderated a 4 hour session where I said four things and had to fight to get those in.”

Imagine there’s a salutory blogging lesson there somewhere.

So I’m walking out of said sesh at the Old Laundry in Marylebone and wander past the very cosy Daunt Books, can’t resist a quick pop-in and come across Paul Arden’s latest by-the-counter tome (the bookshop equivalent of supermarket check-out chocs). Since leaving Saatchi’s he’s been writing rather minimalist bookettes on Creative Thinking such as Whatever You Think Think the Opposite and It’s Not How Good You Are It’s How Good You Want to Be. When I was approached by some bizarre nascent outfit at ITV called Imagine about 18 months ago I read a couple of these to get me back into that zone (creative thinking theory) with which I hadn’t actively engaged that much since writing MindGym (with Tim Wright and Ben Miller). Arden’s latest is all about the Creator rather than creativity – God Explained in a Taxi Ride – and I was quite taken with the first page I opened it at – he suggested the best thing to put on Ground Zero was a big mosque. And I’m inclined to agree. And it really makes you think how thin on the ground Creativity is in political circles. I’ve no idea what Arden’s politics are and whether he’s of the ‘Labour isn’t Working’ era at Saatchi but you can’t help wondering how the world could be with a bit more left-field (whether left wing or not) thinking applied to the pressing problems (and opportunities) of our age…

Je suis un chef noir – Heart of Darkness

Senegal, West Africa – two years before the turn of the 20th Century. A French military expedition sets out from Dakar for Lake Chad in November 1898 with a view of unifying all French territories in the region. The mission involves 50 Senegalese infantrymen, 20 cavalry, 30 interpreters, 400 auxiliaries and 800 porters – well over a thousand men led by nine French officers.

In command was 32 year old Captain Paul Voulet and his adjutant Lieutenant Julien Chanoine. Voulet was the son of a doctor and Chanoine the son of a general and future Minister of War.

Their orders were on the vague side: to explore the territory between the river Niger and lake Chad, and put the area “under French protection”. The Minister of Colonies said: “I don’t pretend to be able to give you any instructions on which route to choose or how you are to behave towards the native chieftains”.

When the expedition reached Koulikoro on the Niger, it split in two. Chanoine led most of the column overland across the 600-mile meander of the river, while Voulet travelled downriver with the rest of the men to Timbuktu.

As Chanoine progressed overland he found it increasingly difficult to find provisions for his large column in the arid landscape so he started raiding the villages along the way. He ordered that anyone trying to escape was to be shot. Adding to these troubles, a dysentery epidemic broke out – by the end of the first two months the mission had lost 148 porters to the disease.

Voulet and Chanoine were reunited in January 1899 at Say, the easternmost post in French Sudan (now in Niger). The column by then was 2,000 men strong – far more than their supplies could sustain. The pillaging and killing grew to match.

On 8th January 1899 the village of Sansanné-Haoussa was sacked. 101 people were killed. 30 women and children were taken prisoner in retaliation for the wounding of two soldiers.

At the end of January the mission left the river Niger for the semi-desert territory to the East.

Around this time, one of the officers, Lieutenant Peteau, told Voulet that he had had enough and was leaving. Voulet dismissed him for “lack of discipline and enthusiasm.” Peteau wrote a letter to his fiancée detailing the atrocities that he had witnessed. His fiancée contacted her local Deputy, who sent her letter on to the Minister of Colonies, Antoine Guillain. On 20th April 1899 orders were issued from Paris to arrest Voulet and Chanoine and have them replaced by the governor of Timbuktu, Lieutenant-Colonel Klobb. (Of particular concern to the French government was that Voulet was operating in Sokoto, an unconquered territory which under the Anglo-French agreement of June 1898 had been assigned to Britain). Klobb immediately set out from Timbuktu with a force of 50 fifty men.

Back in Africa, Voulet was meeting considerable resistance from the local queen, Sarraounia. At Lougou on 16th April his column suffered its biggest set-back to date – a battle in which 4 men were killed and 6 wounded. Voulet took his revenge. On 8th May, in one of the worst massacres in French colonial history, Voulet-Chanoine slaughtered all the inhabitants of the village of Birni-N’Konni, killing hundreds of men, women and children.

Klobb followed the trail of destruction left by the mission – an infernal path of burned villages and charred corpses. Trees where women had been hanged. Cooking fires where children had been roasted. Severed heads on stakes. The remains of those expedition guides who had displeased Voulet – strung up alive in such a position that the feet went to the hyenas and the rest of the body to the vultures.

After a pursuit of over 2,000 kilometres, Klobb caught up with the Voulet-Chanoine expedition just beyond Damangara near Zinder (in present day Niger). On 14th July – French Independence Day – Klobb confronted Voulet at Dankori. In full dress uniform and with his Légion d’Honneur medal pinned to his chest, Klobb approached the renegade Voulet alone. Voulet kept telling him to go back and ordered two salvos to be fired in the air. When Klobb addressed Voulet’s men, reminding them of their duties, Voulet threatened them with a pistol and ordered them to open fire. Klobb fell, wounded, but still ordering his men not to return fire. This final order was cut short by a second burst of fire which killed him.

That evening Voulet informed his officers of the clash. He stripped off the decorations on his uniform and proclaimed: “Je ne suis plus français. Je suis un chef noir. Avec vous, je vais fonder un empire” [“I’m no longer French. I’m a black chief. With you, I shall found an empire.”]

The officers were less than enthusiastic. Their negative reaction spread to the troops. Two days later an informer told Voulet that the men were about to mutiny. Voulet and Chanoine assembled the troops. They shot the informer in front of them all for informing too late. Voulet harangued the soldiers about their duty to obey their leaders, at the same time shooting at them. The Senegalese returned fire, killing Chanoine, but Voulet escaped into the darkness.

The following morning Voulet tried to re-enter the camp, but was blocked by a sentry who refused to let him pass. Voulet shot at him but missed. The sentry returned fire and ended the story of the Voulet-Chanoine mission.

An enquiry initiated by the Ministry of Colonies back in the mother country closed in December 1902, concluding that Voulet and Chanoine had been driven mad by the dreadful heat of Africa.

[This story was first brought to my attention some years ago by my good friend Marcelino Truong in Paris.]

Comments (10)

Comments (10)