Archive for the ‘david hockney’ Tag

Quotation: hands on

After three months of Zooming these words resonate:

A Hockney garden

“Everyone must leave something behind when he dies, my grandfather said. A child or a book or a painting or a house or a wall built or a pair of shoes made. Or a garden planted. Something your hand touched some way so your soul has somewhere to go when you die, and when people look at that tree or that flower you planted, you’re there.

It doesn’t matter what you do, he said, so long as you change something from the way it was before you touched it into something that’s like you after you take your hands away.”

(Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451)

Artistic Devices: Hockney in London 2017

I was working at Chelsea School of Art in Pimlico recently and took the opportunity, after a meeting about a prospective TV programme, to nick into Tate Britain which is directly opposite and see the David Hockney exhibition.

To mark the occasion of this major retrospective, entertaining if a little rammed, I’d like to dig out my Hockney Picture of the Month, Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices, which is in the show of course.

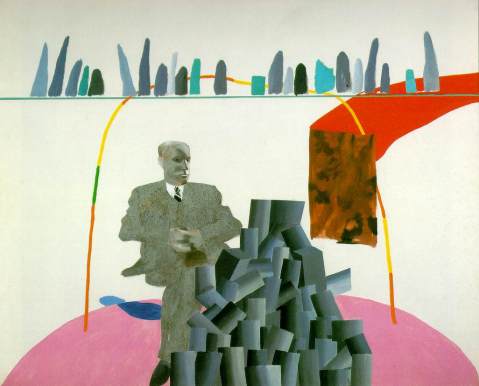

Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices (1965)

And to add an extra something to celebrate the exhibition I’d like to highlight some other artistic devices in evidence in this show. For the significance of ‘artistic devices’ I’ll quote from my earlier post:

The person portrayed is partly obscured by a pile of (obviously painted) cylinders. Above his head is a shelf on which are a selection of large brushstrokes. The cylinders are crude 3D representations, obvious devices or techniques, which stand out as abstract in a still figurative world of suits and rugs and shelves. The shelf is just a 2D line. The strokes on the shelf are more flat, abstract components of painting, exposing the technique and undermining the illusion. The pile of cylinders is actually painted on a sheet of paper glued to the canvas to leave the viewer in no doubt as to the artifice, physical materiality and flatness of the endeavour.

Sunbather (1964) – water devices (although it’s complicated – Hockney had painted lines on his pool floor)

A Bigger Splash (1967) – plant devices & more water devices

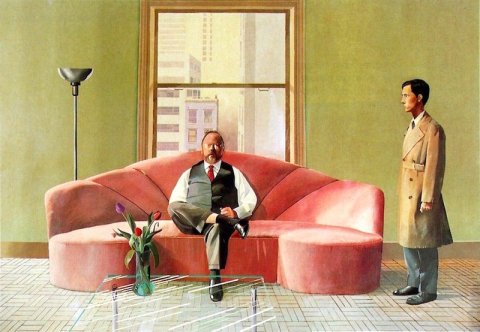

Henry Geldzahler and Christopher Scott (1969) – glass devices

Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy (1970-1) – carpet devices

Marilynne Marilyn – Picture of the Month: The Only Blonde in the World by Pauline Boty (1963)

The Only Blonde in the World (1963) by Pauline Boty 1938-1966

My mum is called Marilynne Marilyn. Not a lot of people know that. My grandfather couldn’t spell the name, got it wrong on the birth certificate, wasn’t allowed to cross it out, so had to have a second go. Marilynne Marilyn is a blonde.

Today I have been reading about Mandy Rice-Davies of Profumo Affair notoriety. Another blonde in the world. Her real first name was actually Marilyn. Not a lot of people know that.

Marilyn Monroe, as the biggest star in the world and the epitome of late 50s female sexuality (at least as far as men were concerned), was a popular subject for Pop artists on both sides of the water.

Marilyn Diptych (1962) by Andy Warhol 1928-1987

Monroe died (or was hounded to her death, as Boty might say – she considered Marilyn “betrayed”) in August 1962 from an overdose of barbiturates. Warhol spent the rest of ’62 creating images of her, all derived from a publicity photo for Niagara (1953). The right-hand half of the diptych speaks of fading and mortality.

Monroe died at just 36. Boty only made it to 28.

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) by Peter Blake

Marilyn features on the centre line of one of the most famous of all Pop images, the one that was actually just a millimetre or two from the pop itself (in the form of black vinyl). She’s just above Ringo and Johnny Weissmuller, swamped in a sea of men.

‘Randy Mandy’ wrote of her bubbly blonde public image: “Every man’s sexual fantasy – it’s a curious role to play in life. I meet men who were schoolboys when my picture was front page news and they greet me as a figment of an erotic dream. There is nothing I can do about this, it has nothing to do with the real me. That Mandy is a pert blonde who is all things to all men. Perhaps that is her secret – she never disappoints.”

Marilyn aka Mandy exiting the infamous trial of Stephen Ward (1963)

The big David Hockney exhibition opens at Tate Britain in a few hours, a retrospective of 60 years of painting. The Hockney generation at the Royal College of Art (at which I’ve been privileged to be working recently, under Neville Brody, Dean of the School of Communication) lusted to a man (bar presumably Hockney himself) after Boty who was every inch the attractive blonde.

Pauline Boty

in BBC Monitor ‘Pop Goes the Easel’ directed by Ken Russell

1963 emulating Hockney’s muse

The blonde in Boty’s painting is far from the only one in the world. The title is ironic. It’s Marilyn. It’s Pauline. It’s Mandy. It’s Diana. It’s any number of fantasy blondes.

Michael Winner directs Diana Dors (28th January 1963)

In ‘The Only Blonde in the World’ Marilyn is contained within a flat, abstract space – both the left and right green panels are higher than Marilyn’s panel. The designs of that space have echoes of Sonia Delaunay’s Orphism which was shown in London around this time.

Sonia Delaunay 1942

The 2D green abstract panels slide open to reveal a glimpse of a ‘3D’ space in which Marilyn positively buzzes with energy. Her famous legs are descendants of Marcel Duchamp’s celebrated Nu descendant un escalier n° 2 (1912).

Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2 (1912) by Marcel Duchamp

I’m not sure where Boty’s Marilyn image is drawn from. Some critics and commentators say Some Like It Hot but I can’t find any such image – I think it may be from the premiere of The Seven Year Itch. It doesn’t really matter where exactly it came from, the point is I’m pretty sure there will be a specific photo out there that she used as a source, one in a magazine, to align with the popular culture focus of British and American Pop Art.

Marilyn and Joe DiMaggio at the premiere of ‘The Seven Year Itch’ (1955)

The vibrating energy of Boty’s Marilyn reflects her genuine admiration of Monroe as a woman mythologised through pop culture. The grey background, which links out to the lines and swirls of the abstract framing image, picks white Marilyn out like a spotlight at a Hollywood premiere. She’s a flash of white brilliance as she crosses the gap. The journey between the two green panels is short but Marilyn still steals the show, as she did in her tragically short life.

Little did Boty know but her own would also be cut tragically short. They found cancer when she went for the first scan of her first child. The brevity of her life has left her to a large extent written out of British art history. ‘The Only Blonde in the World’ is the only Boty in the Tate. Otherwise the only British public gallery holding a Boty is Wolverhampton Art Gallery. The bulk of her paintings languished for many years in a barn. She was an exact contemporary of Hockney (born the year after him). She went to the Big Studio in the sky just three years after capturing’The Only Blonde in the World’. Had she lived and had time to evolve I wonder whether it might have been her massive retrospective opening at Tate Britain tomorrow…

Celia Birtwell and some of her heroes (1963) by Pauline Boty 1938 – 1966

(That’s a young Hockney bottom right having a smoke.)

Celia Birtwell by David Hockney

Hockney in his Notting Hill flat with his friend and muse, textile designer Celia Birtwell (1969)

Birtwell with Hockney in front of his ‘Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy’ (2006)

(Birtwell was married to fashion designer Ossie Clark)

Hockney with Birtwell in ‘A Bigger Splash’, directed by my first boss, Jack Hazan (1973)

Related posts:

The last Picture of Month – also touching on the Profumo Affair

An earlier Picture of the Month featuring a young Hockney at the RCA

A recent Profumo walk related to Mandy aka Marilyn Rice-Davies

The Hope of Pattern

259 Today: Blake’s grave on his birthday

I live for coincidences. They briefly give to me the illusion or the hope that there’s a pattern to my life, and if there’s a pattern, then maybe I’m moving toward some kind of destiny where it’s all explained.

It turned out something of a literary day today. It started with a note on this humble blog from an actor interested in Jean Newlove, collaborator of Joan Littlewood and pioneer of movement as a discipline in theatre. The actor in question appeared as a young Alan Turing in ‘The Imitation Game’, growing up into Benedict Cumberbatch (patron of our very own Phoenix Cinema in East Finchley). I interviewed Jean Newlove, mother of the late Kirsty MacColl (who will be coming in to season shortly as the female half of the greatest of all Christmas songs, ‘Fairytale of New York’), for the Littlewood chapter of my not-yet-finished book ‘When Sparks Fly’.

I was keen to read the last couple of chapters of the excellent novel I’ve been reading the last couple of weeks, Amos Oz’s ‘Judas’, so I left a bit early for my first meeting in Old Street and repaired to nearby Bunhill Fields to read in the low yellow winter sunshine. I sat down by John Bunyan’s tomb, inhaling the roll-up smoke of two Eastern European workers on the adjacent bench, and by way of hors-d’oeuvres downloaded a copy of ‘The Pilgrim’s Progress’ to my phone and read the opening. It’s a good complement to ‘Judas’. I then read some of the wizardry of Oz before heading off to my first meeting with a young scriptwriter of the Paul Abbott school. I’m producing a short film for him. On my way over to Silicon Roundabout I remembered there were other literary types in Bunhill Fields and sauntered past them – Daniel Defoe and beside him the great Londoner William Blake, born in Marshall Street, Soho where my very first job (for a film company) was located. I’d spotted on a Twitter post just after the note from the actor that today was Blake’s birthday. I hadn’t paid much attention but once in front of the grave it came back to me and the coincidence of showing up at his death place on the day of his birth delighted me as I have been much taken with coincidences in recent times.

#OneLostGlove

I’ve had two other good ones in the last couple of days. On Saturday night I was on my way to see Michael Keegan-Dolan’s brilliant dance Swan Lake / Loch nEala when I came across One Lost Glove and photographed it as is my wont with a caption playing on a song title as is my wont: Whole Lotta gLove. I was having dinner first with some friends and as I took my seat in Miz En Bouche in St John Street, Islington over their sound system came a version of Led Zep’s ‘Whole Lotta Love’ covered by a relatively sedate female singer.

Today, after I’d finished the Oz book, I resumed Paul Beatty’s ‘The Sellout’, winner of this year’s Man Booker prize. In it I read this sentence: “Frankly, I wouldn’t be surprised by p values in the .75 range.” I got that it was taking the piss out of a certain kind of academia and social science but I had no idea what p values are, never heard of them before. This evening I’m at a lecture by Ogilvy’s Rory Sutherland (who I also interviewed for ‘When Sparks Fly’) on Behavioural Economics. He mentions p values of course.

![A BIGGER SPLASH [BR 1974]](https://aarkangel.files.wordpress.com/2016/11/0072278.jpg?w=480)

A BIGGER SPLASH (1974)

The first chapter of ‘When Sparks Fly’ is about poet Allen Ginsberg, who was hugely influenced by Blake. The road I crossed to get to Bunhill contains St Luke’s church where I once met Patti Smith, who is also a massive fan of Blake and wrote a song called ‘In My Blakean Year’ (but we talked about two other poets who resided in London, albeit briefly – Rimbaud & Verlaine).

The coincidences, both explicable and inexplicable, are the kind of thing that make life worth living. They suggest pattern, yes, but more importantly they suggest magic.

Picture of the Month – Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices

Exactly a week on from the Oscars triumph of the very English ‘A King’s Speech’, I’ve just been re-watching Colin Firth’s first on-screen stammering in Pat O’Connor’s ‘A Month in the Country‘ (1987) and reveling in the bucolic portrayal of deepest Yorkshire, also a reflection on the art and craft of painting, so my choice this time out is a painting by one of Yorkshire’s greatest sons, David Hockney, and the theme of Hollywood runs through this.

My first job out of college was for film production company Buzzy Enterprises. One of my bosses there was Roger Deakins, pipped to the post last week for the Best Cinematography Oscar by Wally Pfister (for ‘Inception’), Roger’s work on the Coen Bothers’ ‘True Grit’ recently earned him the BAFTA. One of Roger’s partners was Jack Hazan, director of the landmark British cinema verite film ‘A Bigger Splash‘ (1973) featuring Hockney and his circle, including fashion designer Ossie Clark; his wife, textile designer Celia Birtwell; Peter Schlesinger and Henry Geldzahler. The latest user-generated review of it on IMDB is none too flattering but brings me nicely to my picture, Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices (1965). This is what Jaroslaw99 of Michigan makes of the film: “Why was the naked swimmer pressed up to the “window” while two others ate dinner, obvlious? Sometimes I think just because the “critics” or “art aficionadoes” can’t understand art or film, they think it is “deep”. That is what I think of David Hockney (the art was mostly one dimensional like grade school children’s) and the same for this film.”

Portrait Surrounded is very much about dimensions (two and three), representation in art and the border between figurative and abstract painting.

The two things I always liked about Hockney is his profound respect for Picasso (in common with Birtwell whose prints were strongly influenced by Picasso and Matisse) and his cheeky sense of humour. I rank Picasso with Bacon as the two greatest artists of the last century. In this painting the use of the phrase “artistic devices” and their very literal depiction in the painting typify Hockney’s playfulness and deflation of the stuff of “critics or art aficionadoes”.

The person portrayed is partly obscured by a pile of (obviously painted) cylinders. Above his head is a shelf on which are a selection of large brushstrokes. The cylinders are crude 3D representations, obvious devices or techniques, which stand out as abstract in a still figurative world of suits and rugs and shelves. The shelf is just a 2D line. The strokes on the shelf are more flat, abstract components of painting, exposing the technique and undermining the illusion. The pile of cylinders is actually painted on a sheet of paper glued to the canvas to leave the viewer in no doubt as to the artifice, physical materiality and flatness of the endeavour.

Cezanne, one of the fathers of Modernist painting, was keen on the simplification of natural forms into their geometric basics – to “treat nature in terms of the cylinder, the sphere, and the cone” (letter to Emile Bernard 1904). Portrait Surrounded is part of Hockney’s on-going questioning of the received wisdom of Modernist painting in the wake of his spell at the Royal College of Art (with the likes of RB Kitaj) and his struggle to find the right balance between abstraction and figurative art.

The person portrayed in this picture is Hockney’s father and the artist is playing out a battle in it between the technical demands of representing the three dimensions of the physical world and the desire to capture the greater depths of emotion and sentiment, like the feelings one has for one’s parents. In his autobiography Hockney wrote: “the thing Cezanne says about the figure being just a cone, a cylinder and a sphere: well it isn’t. His remark meant something at the time, but we know a figure is really more than that, and more will be read into it… You cannot escape the sentimental – in the best sense of the term – feelings and associations from the figure, from the picture, it’s inescapable. Because Cezanne’s remark is famous – it was thought of as a key attitude in modern art – you’ve got to face it and answer it. My answer, of course, is the remark is not true.”

His observation is typical of the cycle of revolts and reactions of art (as well of teenagehood) – I believe Cezanne was actually referring to landscape not figures so Hockney is actually refuting something created through the Chinese whispers of art education. But that doesn’t really matter, it helps him ‘face and answer’ a key issue for his practice.

In the summer of 1960 the Tate held a large exhibition of Picasso’s work which Hockney visited over half a dozen times and recalls as “a very liberating influence”. He found in it permission for the painter to experiment and move through styles in his artistic journey. Earlier that spring he had visited a one-man Bacon show at London’s Marlborough Gallery. In that he saw a strong stand against pure abstraction whilst retaining an emphasis on directly affecting the guts and nervous system through paint. Bacon’s devices like leaving bare large expanses of canvas to literally expose the workings of painting soon became incorporated in Hockney’s work. His pure abstracts of 1959 (the year he entered the RCA as a post-grad) gave way to the combination of abstract and figurative, and the revealing of the techniques and devices of painting to make clear that painting is not a description of the world perceived through the senses but an interpretation and expression of it in all its complexity, not least of the messiness of emotion. Partly obscured behind the pile of cylinders and partly flattened by his collagey suit, the point of depth of this picture is in the father’s flesh, his Baconesque hands and more still his face and eyes – in fact the two dark points of his eyes, the two one dimensional parts of the painting are the deepest (so Jaroslaw99 of Michigan and I can agree for a moment on the single point of one dimensionality).

In the 3D world I’ve only crossed paths with Hockney fleetingly – both times when reviewing exhibitions in the early 90s, once at the site of that influential Picasso show and the other time round the corner from the Marlborough at the Royal Academy (1995). He projected an attractive combination of Yorkshire homeliness and Californian glamour.

He moved to California the year I was born and in 1965, just after Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices, he made a set of lithographs entitled ‘A Hollywood Collection’. Conceived of as ‘an instant art collection’ for a Hollywood starlet, it includes prints like ‘Picture of a Pointless Abstraction Framed Under Glass’ for which he draws not only the pointless abstraction but the frame and even the reflections on the glass, more playing around with artistic devices in the quest for that sweet spot between the abstract and the figurative where deep feeling and insight reside.

Previous pictures of the month: Mark Gertler / Manet

Leave a comment

Leave a comment