Archive for the ‘africa’ Tag

Mountains of the Moon – Richard Burton, explorer

Mountains of the Moon (1990)

Early in my career I got to read two movie scripts which came in to our office for my boss, Roger Deakins. One was ‘Pow Wow Highway’, the other ‘Mountains of the Moon’. They were both realised and I recall that both scripts were superior to the final films. Roger didn’t end up shooting ‘Pow Wow Highway’ (1989), directed by Jonathan Wacks who mainly directed TV and didn’t do that much directing after this movie. But Roger was DoP on ‘Mountains of the Moon’ (1990), directed by Bob Rafelson of ‘Five Easy Pieces’ fame. The film was about Burton & Speke’s expedition into the heart of Africa in search of the source of the Nile.

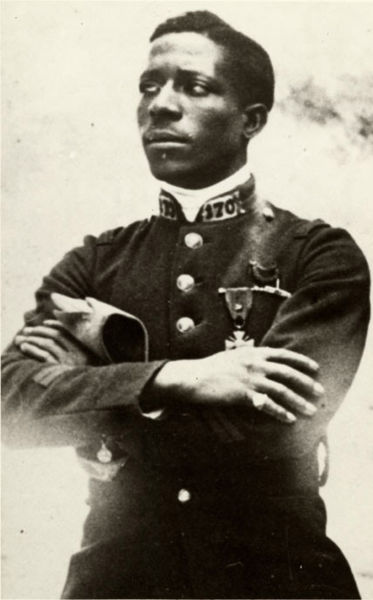

Corto Maltese by Hugo Pratt

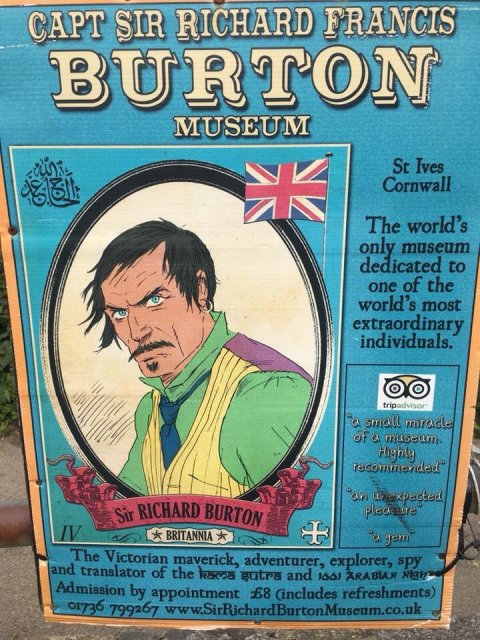

Yesterday I was brought back to these memories by a small poster in a narrow street in St Ives, Cornwall. It was an image of a comic book type character – looking like a cross between Corto Maltese and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen – and information about the Capt. Sir Richard Francis Burton Museum being accessible by appointment only. I rang up and booked a visit the next day (today) at 10am.

At the appointed hour I pitched up with expectations set by a previous experience a bit like this – rooting out a Native American museum in deepest Sussex, in an old forge building in a small village. A real unexpected little gem in the most unlikely spot.

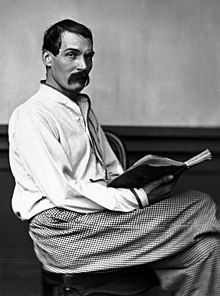

Photo by Rischgitz (1864)

This morning’s arrival was different. The front door of a quiet back terrace house was ajar and in I walked to someone’s home. I was welcomed and shown into a small, square backroom, done up with hints of Arabian style. Faint echoes of Leighton House in London where I used to give art historical tours for charity – Burton brought back Middle Eastern tiles for painter Sir Frederic Leighton’s house and studio in Holland Park. On the walls of this small room were 28 exhibits. My host, Shanty, a professional storyteller, set playing a very well put-together tape which lasted about an hour. Half way through he came back in with a silver pot of mint tea.

Stand-out exhibits included:

Burton’s actual Founder’s Medal from the Royal Geographic Society

The RGS funded Burton & Speke’s expedition and hosted the subsequent contentious debate between Richard Burton and John Hanning Speke about the true source of the Nile – a debate which never happened as Speke died on its eve of gunshot wounds very likely to have been self-inflicted. He was about to be taken apart in public by a highly charismatic man of action cum scholar.

A page of manuscript in Burton’s hand

Written in his dense scrawl, the small page completely covered in script at various angles in ink and pencil. Evidently worked on on at least four occasions with different writing implements. He had 11 desks in his massive study in Trieste in his latter years, each with a different literary or scholarly project upon it. The manuscript all the more valuable as his wife, Isabel, (played by Fiona Shaw in the film, who I found myself standing next to on stage recently at the Festival Hall in the winners’ group photo at the TV BAFTAs) burnt many of his manuscripts in the wake of his death, in particular his just finished translation of the erotic classic from Arabia ‘The Perfumed Garden’. Erotic and Victorian didn’t make easy bedfellows.

Original illustrations of Burton from Look & Learn magazine

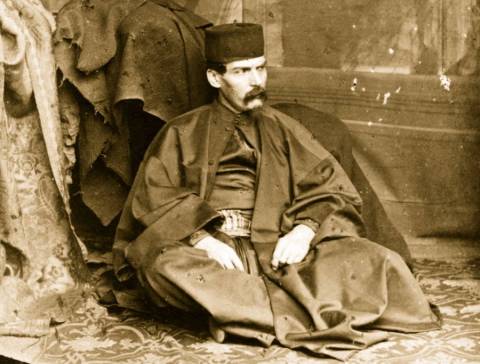

Shanty, whose labour of love the Sir Richard Burton Museum is, has been obsessed with Burton’s extraordinary life and story since he was 14 and got this magazine excitedly among his parents’ incoming newspapers. We were born the same year and I too remember the thrill of receiving this educational magazine for young people, as well as TV 21 (an even bigger thrill, centred on the creations of Gerry Anderson). The illustrations are magnificent, in the same way as those of Ladybird Books and Airfix model boxes were. I imagine these artists are now far more recognised, whereas back then they were largely taken-for-granted commercial illustrators. The main one exhibited here is of Burton going undercover to Mecca as an Arab to become the first white man to reach the heart of the Hajj. He spoke some 25 languages fluently (humbling for an Oxbridge linguist like myself), including Arabic, which he taught himself at Oxford (before being kicked out in his fifth term) and which enabled him to spend six months in disguise as an Arab, infiltrating Mecca at pain of death for any slip.

VHS copy of ‘Mountains of the Moon’

I only saw this movie once, when it came out in 1990. Iain Glen I’ve always really liked, especially after seeing him play a squaddie at the Royal Court in Jim Cartwright’s brilliantly staged ‘Road‘. He played Speke. Burton was played by Dubliner Patrick Bergin. Being non-English was good for the role as Burton only lived in England for 5 years of his entire 69-year life and was never really comfortable with the place. His parents had a streak on Anglo-Irish in them via the British army. He was born in Devon (Torquay) and christened in Elstree, near where I went to school. He is buried in South-West London at Mortlake in a striking mausoleum. (I plan to visit it this autumn, as well as the Elstree church, and will report back.) But otherwise he grew up in Italy and mainland Europe, spent much of his old age in Trieste, and between travelled widely across the Middle East, Africa and beyond.

Proposed 200th anniversary Portrait

One cork-board item contains a proposed portrait of Burton – linking him to James Joyce (who entered Trieste just as Burton left, a similar exile) and the Italian painter De Chirico. It turns out Shanty, like me, is a massive ‘Ulysses’ fan and has noted the various references to Burton in that novel. He has a theory that the date of Bloomsday is related not to Joyce’s lover Nora Barnacle (a popular theory Joyce never confirmed) but to Burton and the date he departed for the interior of Africa.

in disguise

Dressed as a pilgrim en route to Mecca in 1853

The small but perfectly formed collection is certainly worth a visit, a well told digest of the life of an extraordinary polymath or Renaissance man – one with a unique balance between man of action and scholar, a linguist cum swordsman, a diplomat cum satirist, mesmeric, astonishingly handsome, a true Romantic hero of the highest order.

Comments (1)

Comments (1)